By Stefano Riela

Stefano Riela asks how big the economies are of authoritarian regimes.

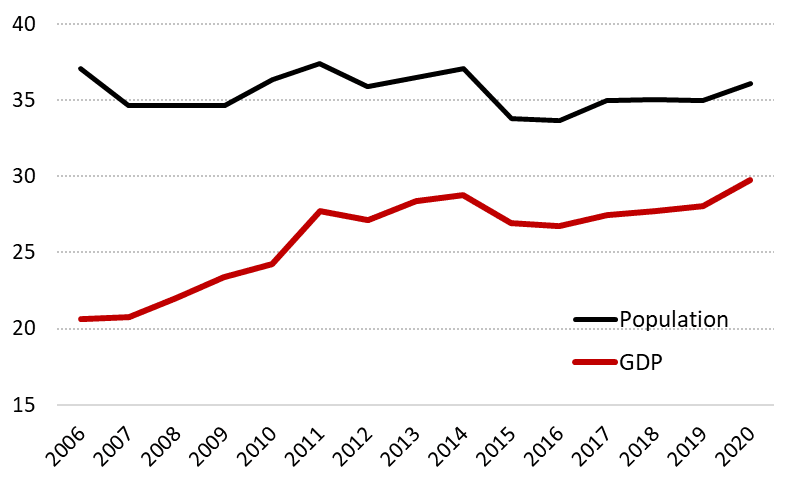

The economy of authoritarian regimes comprises 30% of the World economy (see the red line in the figure). This percentage is on the rise, in contrast to what Francis Fukuyama predicted in his bestseller The End of History and the Last Man (1992): the Western model of liberal democracy will eventually triumph after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War.

Graph: GDP and population of countries with an authoritarian regime (% World total)

According to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), that has recently published the Democracy Index 2020, in authoritarian regimes “ [ …] state political pluralism is absent or heavily circumscribed. Many countries in this category are outright dictatorships. Some formal institutions of democracy may exist, but these have little substance. Elections, if they do occur, are not free and fair. There is disregard for abuses and infringements of civil liberties. Media are typically state-owned or controlled by groups connected to the ruling regime. There is repression of criticism of the government and pervasive censorship. There is no independent judiciary.”

Truth be told, Fukuyama expected the triumph of liberal democracies in long run; but the short run could still be punctuated by setbacks like those in September 2001.

Two decades have passed since that September 11th, but those few seconds are still a vivid memory of how religious beliefs can subvert the ranking of values, topped by the love for terrestrial life, crystalized not only in Western liberal democracies. Less known is what happened six days after: on September 17th 2001 the World Trade Organization (WTO) concluded the negotiations on China’s terms of accession. The view, reflected on the official protocol, was that entering an international organisation born to promote free and fair trade would have triggered a process of assimilation; China would have turned from a non-market economy into a market economy where the economic freedom is generally understood as the perfect match for a liberal democracy.

Why that specific reference to China? Because China is the largest authoritarian regime (followed by Russia, Saudi Arabia and Egypt) and has a strong GDP performance: China’s economy was 7.7% of the world total in 2001 and it will be 19.1% in 2021. While China’s economy was booming, other big countries ranked by the EIU as full and flawed democracies reduced their economic weights: the US, Japan, Italy, Germany, France, the UK, Spain, Canada, and the Netherlands. (Australia and New Zealand have kept the weight they had twenty years ago).

In 2020, the global average of the Democracy Index hit an all-time low and almost 70% of countries recorded a decline in their score also due to government-imposed restrictions on individual freedoms and civil liberties that occurred across the globe in response to COVID-19. In particular, according to the EIU, some governments saw a drop in their score because they censored lockdown sceptics, and these “attempts to curb freedom of expression are antithetical to democratic principles. The withdrawal of civil liberties, attacks on freedom of expression and the failures of democratic accountability that occurred as a result of the pandemic are grave matters”.

Hopefully the tough restrictions due to COVID-19 will be over, but we will have to prolong that long run envisaged by Fukuyama beyond that process of assimilation expected by the WTO twenty years ago.

Stefano Riela is an Honorary Research Fellow at the European Institute of the University of Auckland. He is an expert in European integration and EU trade policy.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

Has the COVID-19 crisis pushed solidarity in the European Union?