By Stefano Riela

Has the COVID-19 crisis pushed solidarity in the European Union? Stefano Riela explores.

It was one of the longest European Council meetings. From Friday 17 July to Tuesday 21 July, five days and four nights in Brussels during which the 27 EU heads of state and government had to find a common position on two elements: the first is the ordinary EU budgetary plan for the expenditures and revenues from 2021 to 2027 (the multiannual financial framework, MFF); the second, the new extraordinary instrument to help countries recover from the COVID-19 recession (named Next Generation EU).

The 27 leaders could have not postponed the decision on the new MMF any longer since 2021 is a few months away and the EU should have clarified its future financial commitments. With regard to the COVID-19 crisis, the EU as a whole is experiencing the worst recession ever (the GDP is expected to drop by -8.3% in 2020) but some countries have been hit harder than others with estimates ranging from -11.2% in Italy, -10.9% in Spain, -10.6% in France, to -6.8% in the Netherlands, -5.3% in Sweden, -5.2% in Denmark and -4.6% in Poland.

The length of the summit can hardly be attributed to the joy of the 27 leaders to meet in person, though masked and distanced, after months of video calls. Those five days were needed to hammer out a position to approve unanimously. However, the 27 leaders arrived in Brussels divided along different lines especially for the brand-new Next Generation EU.

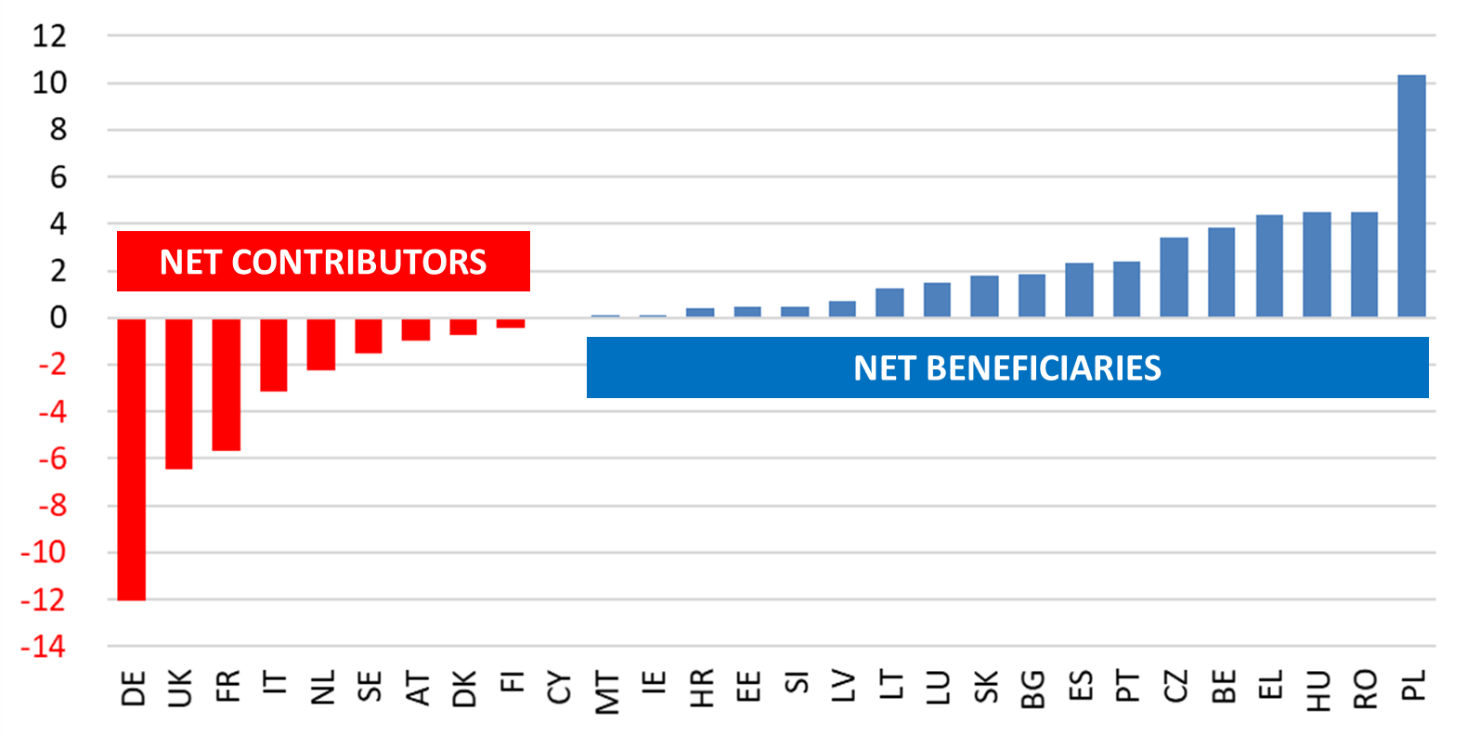

Among the internal divisions, the ‘frugal’ countries – the Netherlands, Austria, Sweden and Denmark – were in favour of a relatively lower EU expenditure (the exit of a net contributor like the UK has not helped); higher weight on loans, rather than non-repayable grants, to the countries in need; and more stringent conditionality for the beneficiaries. What the four frugal countries have in common is that they are net contributors to the EU budget (Figure 1), i.e. their “operating budgetary balance” is negative since their respective national contributions to the EU budget are larger than the EU expenditure in each country to support agriculture, research and development, poor regions etc.

Figure 1 – Annual operating budgetary balance (average 2014-2018, billion euro)

Though “operating budgetary balance” cannot fully capture the benefits of being part of the EU (such as the stronger bargaining position when it comes to international agreements such as in trade, the advantages of the single market with its free mobility of workers and students, services and goods, and capital), the frugal four were worried that the additional EU expenditures would have exacerbated their negative balances.

Eventually a deal was reached on a spending package worth 1.8 trillion euro designed to allow all 27 leaders to get back to their respective capitals without losing face in front of their voters and without being humiliated by their opposition.

The size of the expenditure, that if annualised, is not even 2% of the GDP of the EU-27, reveals a jump on the front of intra-EU solidarity. However, along with remarkable novelties, this deal perpetuates some old weaknesses.

EU debt for the first time

For the first time there will be a sizeable EU debt. The Next Generation EU involves the European Commission borrowing up to 750 billion EUR in the financial markets that will be distributed to members as grants (390bn) and as loans (360bn). Truth being told, there was already some EU debt created when Ireland and Portugal were supported at the onset of the sovereign debt crisis of the last decade. Moreover, there is some joint debt in the Euroarea realm, with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) created during the last debt crisis to provide financial assistance to countries in difficulty. Even though this EU debt is linked to a one-off emergency fund, it will be a relief for highly indebted countries (such as Greece and Italy with 196% and 159% of their respective GDPs) and it will offer financial markets a long-coveted-continental-risk-free asset.

Help comes with strings attached

The Next Generation EU funds will be distributed to members according to the economic harm done by the pandemic. Governments will have to submit spending and investment plans to the Commission, which will evaluate them. However, other governments can block the financial transfers to a country if it is failing to fulfil its reform promises in return for the money it is receiving from the Commission.

Sorry Greta, the future can wait

To keep the EU expenditure under control after the COVID-19 crisis, the EU leaders had to scale-back future-oriented programmes in MFF such as in the fields of research, health-care and climate adjustment. A big EU expenditure such as agriculture will be almost untouched. This might help to win farmers’ support for the free trade agreement currently in negotiation between the EU and New Zealand.

All EU members are equal, but some are more equal than others

Where is the money coming from? The deal mentions new resources but only a levy based on non-recycled plastic waste is concrete. There will/could be proposals for a carbon border tax, a digital tax, a Financial Transaction Tax, and the sale of carbon allowances under an Emissions Trading System possibly extended to aviation and maritime sectors.

While waiting for those new resources there one is certainty. Along with the new EU debt, the money for the MFF will mainly come from the 27 member States according to their Gross National Income (GNI). Different discounts to those national contributions have been granted to specific countries to guarantee more fairness. This was the case of the “rebate” obtained by the UK in 1984 when an agriculture-centric EU budget was of no interest to the hub of the Commonwealth.

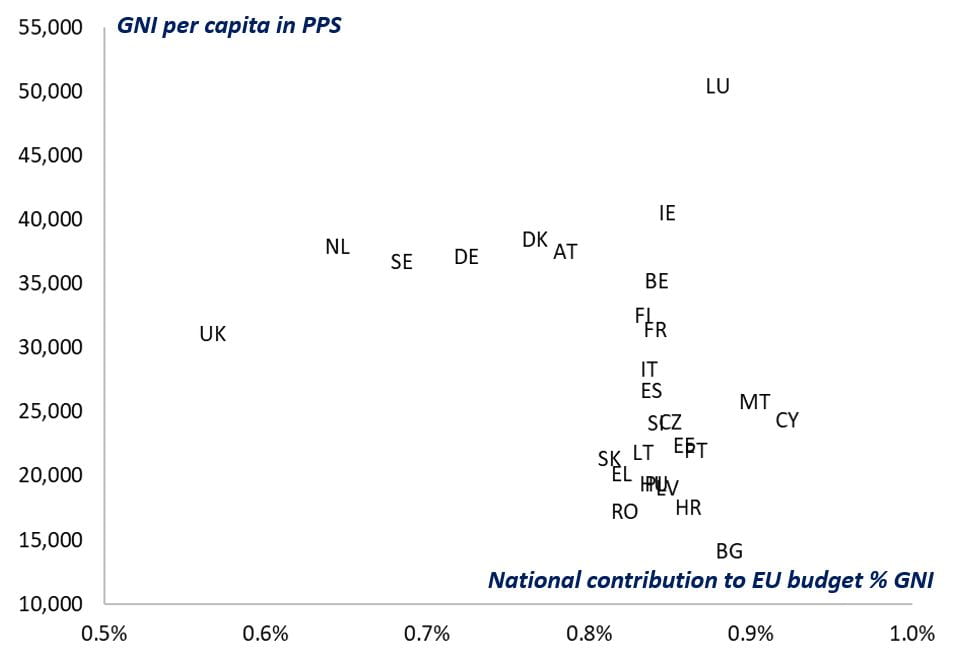

However, those special concessions led to a picture that can hardly be defined as fair. In Figure 2, countries with similar levels of GNI per capita in purchasing power standard (PPS) contribute differently to the EU budget (see, for example, the Netherlands and Belgium). At the same time, countries with a similar level of contribution to the EU budget sport different levels of GNI per capita in PPS (see, for example, the case of Luxembourg and Bulgaria, with the former more than three times richer than the latter).

Figure 2 – National contributions to EU budget (% GNI) and GNI per capita in PPS (average 2014-2018)

The final deal has significantly increased the rebates for the four frugal and Germany, i.e. the future national contributions of these countries will be relatively less than today. This special treatment for these net beneficiaries will not make the revenue system any fairer, but it was necessary to buy the approval of the frugal four to reach the deal.

Now the ball is in the court of the European Parliament

The deal was approved by the member States, but now the European Parliament (EP) should give its consent on the MFF 2021-2027 to which the Next Generation EU is tied. In a resolution approved on Thursday 22 July, the majority of the members of the EP showed that they are not ready to rubber-stamp the deal just reached by the European Council; they are asking for more generosity to restore significant expenditures on the future-oriented programmes. Should the EP withhold its consent, the 27 leaders need to get together again and, this time, be ready for the longest European Council meeting ever.

For more information on COVID-19, head to the Ministry of Health website.

Stefano Riela is a research fellow at the Europe Institute, The University of Auckland. Stefano is an expert in European integration and EU trade policy.

This article is published as part of a series commissioned by the Europe Institute at the University of Auckland.

For more on the Europe Institute, click here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

Will Covid-19 change access to essential goods?

Is German creativity, solidarity and the odd Berlin graffito an answer to COVID-19?