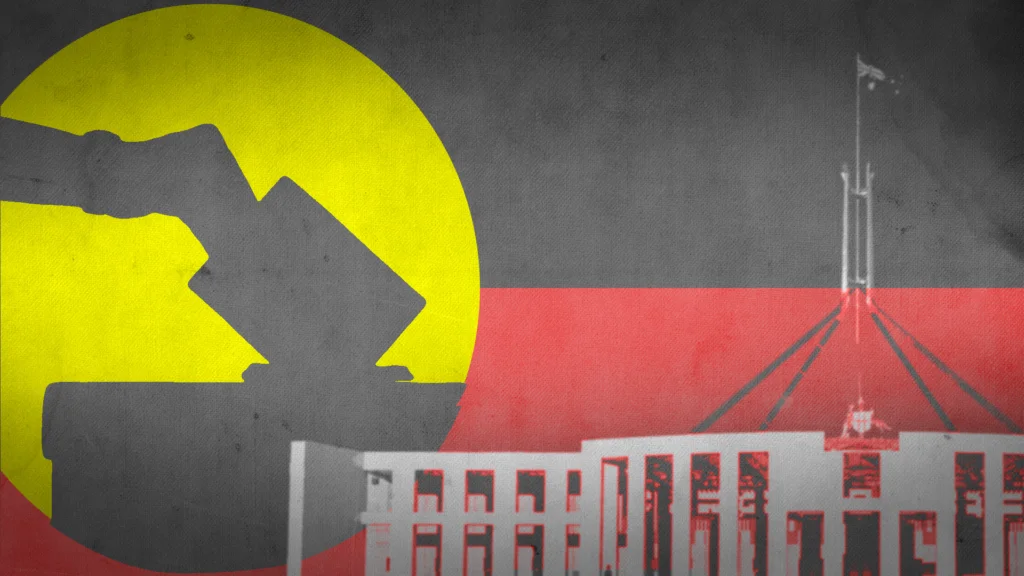

On 14 October, Australians voted in a referendum to amend their constitution. They were asked to write ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to the following question:

“A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

The result was a resounding “no”. The referendum question stems from the requests made in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, a document signed by 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders at a constitutional convention in 2017. It called for the establishment of a ‘First Nations Voice’ in the Australian Constitution.

The referendum question lay dormant until 2022, when new Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced he would put the question to the people within his first term in office. Since then, Albanese’s government and an Indigenous Voice to Parliament have been inextricably linked, the success or failure of the referendum becoming tethered to the political fortunes of a new prime minister. It carried political risk. Referenda don’t have an excellent record in Australia, with just eight being successful from 44 attempts. The most recent successful vote was in 1984.

A year ago, support for the referendum sat at around 65 percent. However, a week from the vote, the constitutional amendment seems unlikely to succeed. According to John Evans of Swinburne University, the length of the campaign has harmed its chances.

“I think giving such a long gestation period towards the vote means that the No campaign can really mobilise and create doubt in Australian people about what the voice is, how it’s going to work and what it means for Australian society,” he said.

Helming the No campaign is Australia’s Opposition Leader, Peter Dutton, backed by the majority of his conservative Liberal Party. Flanking Dutton prominently in supporting the No vote have been two Indigenous Australians, Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price and campaigner Warren Mundine. Both are tightly linked with conservative think tanks. Separately, what has been dubbed the ‘progressive ‘No’ campaign’ has emerged, led by independent Senator Lidia Thorpe, who split from the Australian Greens over the party’s support of the referendum.

The debate has become mired in partisan fighting, with both campaigns accusing the other of racism, misinformation and misleading the public. University of Sydney’s Duncan Ivison said the Indigenous Voice referendum debate “has been marred by fear.”

The hostile tone of discourse has troubled many, as television debates between elected officials descend into heated arguments.

And when the public pick up their phones, they’re seeing more polarised social media feeds affected by algorithms known to promote divisive content.

Micah Goldwater and Joanne Gray from University of Sydney compare the degree and spread of disinformation ahead of the 14 October vote to the COVID-19 pandemic:

“Despite the vast differences between the pandemic and the referendum, the playbook used by disinformation merchants is strikingly similar.”

“The goal of disinformation campaigns is to prevent rational debate. When an issue of national consequence like the Voice referendum arises, having space for clear, thoughtful discussion is important for a functioning democracy.”

University of Adelaide’s Victoria Fielding believes sowing discontent doesn’t stop with online provocateurs.

“Social media often shoulders much of the blame for muddying the public sphere with hate and misinformation, but Australia’s mainstream news media also failed to deliver accurate, quality information about the referendum,” she said.

Her report for advocacy group Australians for a Murdoch Royal Commission claims the Murdoch family-run News Corp disproportionately platformed No campaign arguments, making it “harder for the public to access diverse views.”

When the Australian Electoral Commission said in August it would not consider an ‘x’ marked on a ballot paper as a formal vote, Dutton claimed on national radio: “Australians just want a fair election, not a dodgy one, and I don’t think we should have a process that’s rigged.”

He repeated his concerns on national television, calling for a fair process and accusing the Prime Minister of “loading the system and trying to skew it in favour for the yes vote.”

It sparked debate online over the fairness and legitimacy of the vote. However, the electoral commission’s policy has been the standard since 1988, rejecting the criticism as “based on emotion rather than the reality of the law.”

Regardless of the result on 14 October, reviewing the performance of Australia’s institutions during such a vexing cultural moment may uncover some exploited vulnerabilities.

Within a cacophony of competing interests, the Australian people have been asked one question: “Do you approve this proposed alteration?”

However, it may be hard to hear the question above the noise of everything else.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.