Words by Julianne Evans

Photo by Thomas Schweighofer on Unsplash

Covid has fundamentally changed how people view the environment, their relationship to it and their vision for the future, according to new research from Waipapa Taumata Rau, the University of Auckland.

An appreciation of the environmental benefits of lockdowns, concern about how Covid-related products have contributed to waste and hopes for a greener, pandemic-proof future are key findings of a national survey at the University of Auckland.

Research fellow Dr Komathi Kolandai and a team at the Faculty of Arts’ COMPASS Research Centre, notably centre director, Associate Professor Barry Milne, designed five measures to find out people’s Covid-related experiences and perceptions.

We found that even those with a low interest in the environment were concerned about the negative impacts of Covid on the natural world.

They wanted to know how people felt about the results of a break in human-created environmental impact (the Anthropause); their philosophical thoughts about nature and the pandemic; their feelings about nature and being shut off from it during lockdown (biophilia); their concerns about the pandemic’s adverse global environmental impacts and their hopes for the future of the planet.

They included these questions into the New Zealand version of the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) Environment questionnaire, which measures general environmental perceptions, values, and behaviour while also collecting a range of demographic details.

The survey attracted 993 respondents, which was weighted to represent the New Zealand population and sampled from the electoral roll.

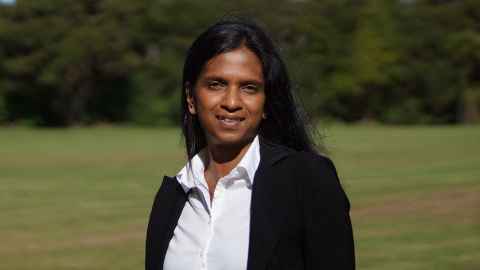

Research fellow Dr Komathi Kolandai: “We saw the importance of pauses in life to contemplate our relationship with nature.”

During lockdowns that confined people to their homes or neighbourhoods, more than a third (35%) of respondents experienced an extreme attraction to nature, while nearly half (47.5%) experienced this moderately, says Dr Kolandai.

“And more than a quarter (26.8%) had philosophical thoughts about nature and the pandemic, while a majority (62.6%) thought about this moderately.”

She says financial and mental health impacts due to Covid had no bearing on people’s perceptions and views about nature.

“Our findings also suggested these experiences were not restricted to those who were already environmentally inclined, but rather experienced broadly in society.

“For example, we found that even those with a low interest in the environment were concerned about the negative impacts of Covid on the natural world [plastic waste, masks, packaging, hand sanitiser].”

Kolandai says while the health and social impacts of Covid have been the primary focus so far, the pandemic also taught us some crucial environmental lessons.

“Because people have directly observed the benefits of a pause to environmentally detrimental activities, they appear to be more supportive of ways of living that can lead to similar outcomes post-pandemic.”

“This pause in human activity made the outcomes of environmental solutions less abstract and showed what can be achieved now, rather than in the future, or for future generations.”

The study found that even those with a low interest in the environment were concerned about the negative impacts of Covid on the natural world.

She says the fact that people had more nature-related philosophical thoughts during Covid suggests the ‘Anthropause’ inspired greater awareness of the centrality of the human-nature relationship.

It was also clear that people aspired to a greener post-pandemic future and supported a range of measures to achieve it; but to be successful, they need the structural support.

“For example, our study shows the public widely supports working-from-home as an emission reduction measure, but its feasibility depends on governments funding more childcare options and employers offering subsidies to support workers’ IT needs.”

The study also showed people were supportive of limiting the chance of another zoonotic pandemic (disease transmitted from animals to humans) by putting a global ban on wildlife trade and consumption, banning factory farming and moving towards plant-based agriculture.

Kolandai believes the study confirms that the enforced break in human impact on the climate offers an environmental baseline for advocating for conservation.

“We also saw the importance of pauses in life to contemplate our relationship with nature.

“Rather than solely focusing on economic recovery, policymakers should acknowledge these pandemic-induced changes in environmental thinking and support the social transformations that could result from it.”

The study’s findings are published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology and Environmental Development.