By Arindam Basu

A long summer awaits India and the world will need to come together to solve the crisis. None of us are really safe until all of us are safe from COVID-19. One hopes that the Indian experience has taught the world this lesson.

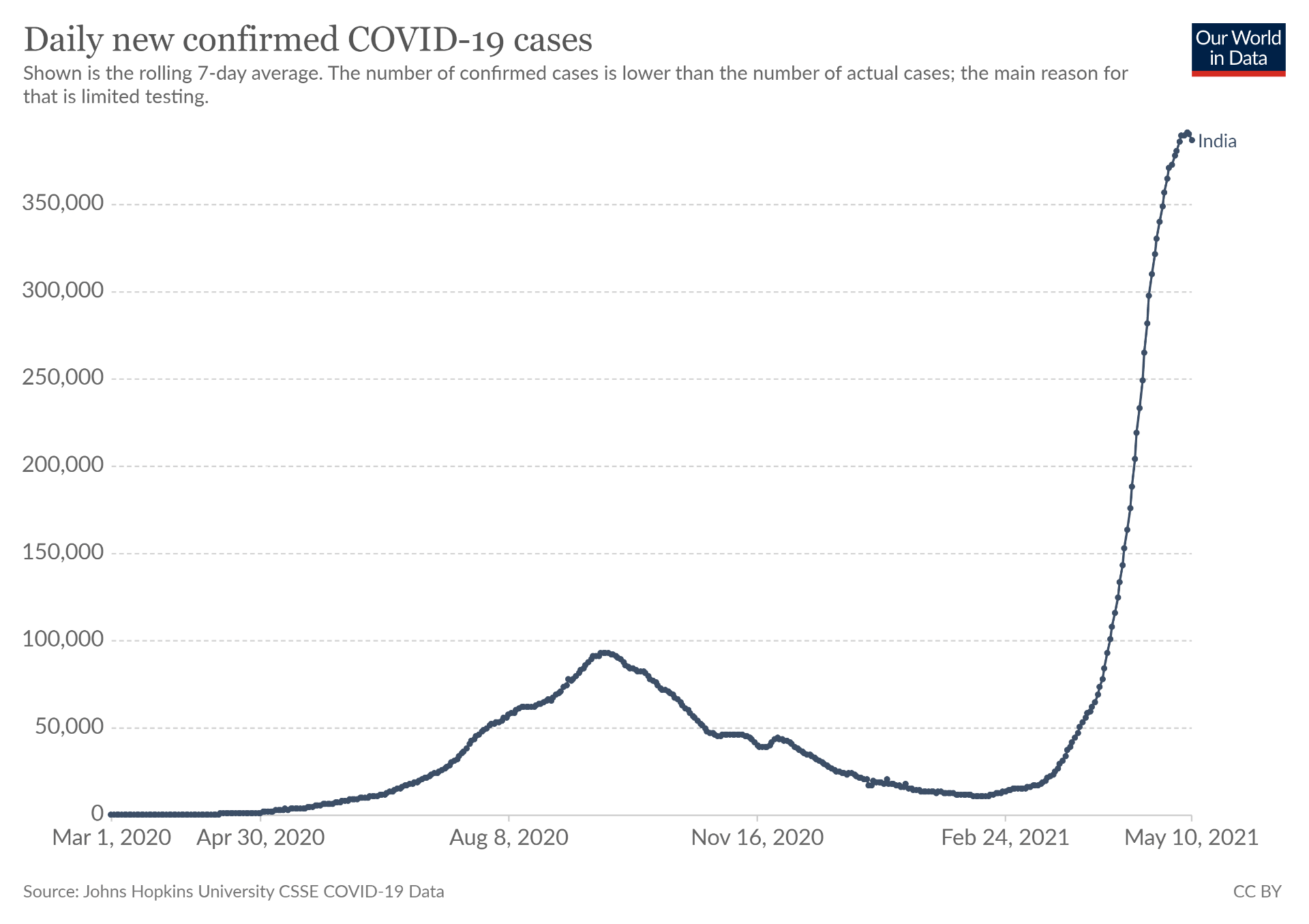

As of 10 May, 2021, India registered about 400, 000 new positive cases a day of COVID-19 for several days at a stretch, with nearly 23 million total COVID-19 cases in the country since the beginning of the pandemic, and almost 80% of cases occurring between March and May of 2021. At the time of writing this, the surge in the number of cases continue (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: India COVID cases

In parallel with this rapid surge in the number of cases, India has also experienced about 4,000 deaths per day between March and May of 2021 and the surge in the number of people dying from COVID-19 continues. It is believed that these numbers are under-reported on the order of about 5-10 times of what has happened in India (Figure 2). Altogether, since the beginning of the pandemic in about February 2020 when India was first hit, nearly 250, 000 people have died due to COVID-19. Between February of 2020 and January of 2021, about 150, 000 people died, and about the same number of deaths were registered in three months since then, such is the ferocity of the new surge or wave of the infections.

Figure 2: India COVID deaths

After India’s first cases were registered in February 2020, for a relatively long time, the number of cases was low and so was the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 although it was known by then that India was not conducting enough tests and was possibly under-reporting the deaths. The first uptick in the number of cases started in the middle of March 2020. Around that time, the Indian government announced a sudden country-wide “lockdown”, apparently without much advanced preparation or allowing people enough time to adjust their lives. Mass transit facilities such as airports were closed, and train and bus services were suspended for a month, as happened with offices and banks, and markets were also closed. People were advised to work from home; most worksites were closed for business, and work in construction sites was halted.

Thousands of migrant workers in the country found themselves out of work and their source of income; with practically no social support provided. Employers laid off these temporary workers with no compensation. Desperate for survival, these workers breached the lockdown conditions and started moving out of cities and started heading home, most people started marching long distances from North Indian cities such as New Delhi to reach their homes in villages of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar, often walking for weeks. The crisis came to a point where the United Nations Human Rights Chief warned India and the world on his blog. This was beyond a humanitarian crisis, and serious as it may be, it also resulted in an unprecedented series of events that may have further augmented the spread of COVID in India within months.

The testing rates in India were among the lowest in the world for a long time. As a result, even with low testing statistics, and under-reporting of cases, India nevertheless registered a steady increase in the number of new cases of COVID-19 throughout the summer of 2020 despite repeated lockdowns and variations of lockdowns and stringent measures enforcing social distancing, and restricting the movement of people. Over time, the testing rates increased, people became habituated to wear masks all time, travelled less on public mass transits, and maintained social distancing.

Starting in the middle of October and continuing into November of 2020, the number of COVID-19 cases started dropping in India. Some hailed it mysterious, and international media hailed the phenomenon as puzzling. Many experts tried to explain that India reached herd immunity – a concept in epidemiology where when a certain percentage of the population reaches a level of immunity either through infection or vaccination, and the rest of the population is protected as the infection cannot propagate anymore – at least in places like Delhi, experts claimed, on the basis of community surveys that suggested certain levels of antibodies to COVID. But the story was far from over at this stage, as subsequent events unfolded, even as experts and India’s habitually glib political leaders and ministers basked in vainglorious claims of early success.

Around December, when the cases started reportedly dropping in numbers in some parts of India and showed up in the statistics charts reported by the country, worldwide new variants of the sars-cov-2 virus were emerging. This was nothing new. The sars-cov-2 virus is known to mutate roughly twice per month, and these mutations are tracked and a database maintained by the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) as part of global influenza tracking system.

However, these new variants were reported from Southwest England in late December and soon rapidly spread to other countries. New, more virulent strains were reported within the Indian state of Kerala as well, and cases were rising even as cases were reported to drop in India overall, and this drop dominated the news. Reportedly, by the end of 2020 and into 2021, India’s testing levels slowed down, people seemed to “drop their guard”, with wearing of masks becoming less frequent. People started travelling in mass transit more, and the government allowed and actively encouraged large mass gatherings in religious festivals and large multi-phased elections in three states of the union. Airports were open and air travel was allowed between India and other countries. There was no provision of mandatory quarantine in the airport or at the borders, such as the system that exists in New Zealand, where majority of the new cases in the country were reported in managed isolation and quarantine facilities and among people entering the country from overseas. In India, on the other hand, any visitor could walk through the border security with routine tests and questions, there was no provision for mandatory isolation and quarantine was in place.

The first COVID vaccine approved for usage in India was the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine that was manufactured by the Serum Institute of India under the trade name of Covishield, and India started administering the vaccines on 16 January, 2021. India approved two vaccines for general usage, one developed within India by the Hyderabad based Bharat Biotech, referred to as “Covaxin”, and the other, the aforementioned “Covishield”. On 1 May, 2021, India received a third, a Russian Sputnik V vaccine for distribution. It is reported that while India exported about 66 million doses of vaccine to 72 countries, it was not prepared with enough doses to cover its entire eligible population with two doses of the vaccines.

Even as the COVID cases from new variants started increasing in various parts of the country, the Indian government mismanaged vaccine distribution, and people dropped their guards. India’s political leaders and rulers were even more reckless. Despite neither planning nor implementing a vaccine programme that would be adequate to vaccinate eligible at-risk people in the country, with no established forward and reverse contact tracing programme in place, relatively low levels of testing, and upon observing a reportedly reduced level of COVID positive cases in the community in the country, Indians seemed to declare a premature victory over COVID. This ignored the rising cases in the states of Kerala and Maharashtra, and a sense of overconfidence and recklessness set in.

On 28 January, 2021, even India’s prime minister Narendra Modi proudly declared at the World Economic Forum Davos Dialogue via video conferencing that “India’s stats cannot be compared with one country as 18 per cent of the world’s population lives here and yet we not only solved our problems but also helped the world fight the pandemic”. If this was a sign of overconfidence, about the time when the so-called COVID tsunami was about to hit, India’s health minister Harsh Vardhan declared at a medical conference in New Delhi in India on the fourth of March that “We are in the end game of the COVID-19 pandemic”. As he declared this, India was only able to vaccinate at that point about less than three percent of their population.

Beyond this, the government of India abetted and orchestrated large gatherings of millions of people in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Between March and May, multi-phased elections were organised in three states of the country. The prime minister, the home minister and other political leaders addressed large gatherings of voters in political rallies and gloated on social media about the enormity of the crowd they addressed in their political rallies. Photographs of such gathering revealed that hardly anyone wore masks at such mass gatherings and these ended up as superspreading events, which were followed by a further escalation of cases in the country.

A second large gathering of people happened in Haridwar, a city in the state of Uttarakhand. Kumbh Mela is one of the largest religious fairs among Hindus that draws millions of people from all over India. In March 2021, more than three million pilgrims from all over India converged in the town of Haridwar in the Uttarakhand state of India, where mendicants and pilgrims converge on the banks of the river Ganga for bathing for several days; people live in small, poorly ventilated tents. Both these events were marked by hundreds if not thousands of people huddled over closed areas, large crowds, and infected people in close proximity to susceptible people – three conditions that lead to upticks in the probability of COVID-19. It was little wonder then that soon after, the number of new cases increased to well over 300,000 every day.

As a result, between the end of February 2021, when the leaders were basking in their tall, if not somewhat vainglorious claims of having solved the world’s problem of COVID and helping the world, and middle of May, India was hit by a so-called “tsunami” of new COVID-19 variants that had never been seen before. As the old strains of sars-cov-2 started declining in the country, the variant B.1617 rose steadily and underwent other lethal mutations. Even with allegedly under-reporting on the total number of new COVID positive individuals, as can be seen from the reports, nonetheless, a near vertical steep rise in the number of new infections of COVID-19 were seen from India.

In parallel, a similar steep, nearly vertical rise in the number of people who have died from COVID-19 in India every day was observed and continues at the time of writing. On an average, everyday in India, more than 350, 000 new cases of COVID-19 are reported, and about 4,000 people die from the disease. As this march of death of COVID-19 continues unabated across India, not a family is spared where death and COVID have not touched yet in this massive country of over a billion people.

India has vaccinated about 2.6% of its total population, which regardless of the total number of people vaccinated, is still far short of what would have been useful or even comparable with countries of similar size and population, such as China, that were able to vaccinate about 30% of their population. The vaccines are in short supply, oxygen supplies are depleted in the country, and people literally begged on social media in search of oxygen, medicines and hospital beds. Hospital beds have overflowed; streetside cremations have been observed as never before in India in a hundred-years. Dead bodies have been set afloat in the Ganges river in hundreds. India is a sad place right now, shattered and devastated.

This is beyond a humanitarian emergency and disaster of unprecedented proportion for India, and now it threatens to spill over to the rest of the world. Surges of cases in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Pakistan are already being reported. As I write this, the World Health Organisation has announced that the variants of the sars-cov-2 virus, B.1617, that has run rampant through India are variants of concern. These variants have already spread to more than 30 other countries. India’s problem therefore goes beyond a mammoth public health emergency and disaster within South Asia but it has now touched the rest of the world significantly, and perhaps no country is now immune from the impending viral spread.

What may have happened and what can be done? In summary, a pervasive misunderstanding and failure to communicate among the general population, but also among leadership in India about the characteristic of the virus and its spread seem to explain the response pattern and rise of infections and deaths. COVID-19 follows a pattern of over-dispersion with isolated clusters where a few people spread the disease among many and most people spread the disease to one or two and the disease spreads rapidly when the clusters merge and grow.

Therefore, lockdowns need to be carefully planned and timed with an eye to allow appropriate “ring-fencing” of the infections. This was not achieved in India in the first place. India continued to under-report the extent of the infection and death rates in the country and this led to a false sense of complacency among the leadership and the mass. Personal practices such as wearing of masks waned in the wake of an observed drop in the infection rates. The infection rates abated but did not go away completely and there were clusters that remained hidden or people with infection that were never reported who later led to more clusters leading eventually to the outbreak. The rollout of vaccination has been very slow in India and the pandemic has been fueled by the massive crowd gatherings.

In the weeks to come, India will need to address these issues. Vaccination rates will need to be ramped up. While on the one hand, those who are suffering need to be taken care of, equally, targeted lockdowns that can ring fence clusters with reverse contact tracing to trace out the network of cases need to be urgently established. A map of superspreading events and circumstances may be helpful in forward planning to prevent further escalation of this pandemic in India which is already very fragile. A long summer awaits India and the world will need to come together to solve the crisis. None of us are really safe until all of us are safe from COVID-19. One hopes that the Indian experience has taught the world this lesson.

Arindam Basu is an Associate Professor in the Education, Health and Human Development faculty at the University of Canterbury. His primary research includes clinical medicine, education, environmental health, epidemiology, health services research, information technology, and interdisciplinary research related to these areas.

For more information on COVID-19, head to the Ministry of Health website.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

A new India emerging? Explaining Modi’s victory in the world’s largest democracy