By Andrew Balemi

From now until October 17, Election Day in New Zealand, voters will be getting election poll information from multiple directions. So which ones can be trusted? The easy answer is: none of them. However, some polls are worth more than others.

Assess their worth by asking these questions:

Who is commissioning the poll?

Is this done by an objective organisation or is it done by those who have a vested interest? Have they been clear about any conflict of interest?

How have they collected the opinions of a representative sample of eligible voters?

One of the cardinal sins of polls is to get people to select themselves (self-selection bias) to volunteer their opinions, like those ‘polls’ you see on newspaper websites. Here, you have no guarantee that the sample is representative of voters. “None of my mates down at the club vote that way, so all the polls are wrong” is a classic example of how self-selection manifests itself.

How did they collect their sample?

Any worthy pollster will have attempted to contact a random sample of voters via some mechanism that ensures that they have no idea who, beforehand, they will be able to contact. One of the easiest ways is via computer-aided interviewing (CATI) of random household telephone numbers (landlines), typically sampled in proportion to geographical regions with a rural/urban split (usually called a stratified random sample). A random eligible voter needs to be selected from that household – and it won’t necessarily be the person who most often answers the phone! A random eligible voter is usually found by asking which of the household’s eligible voters had the most recent birthday and talking to that person. But the fact that not all households have landlines is an increasing concern with CATI interviewing. However, in the absence of any substantiated better technique, CATI interviewing remains the industry standard.

What about people who refuse to cooperate?

This is called non-response. Any pollster should try to reduce this as much as possible by re-contacting households that did not answer the phone first time around, or, if the first call found the person with the most recent birthday wasn’t home, trying to get hold of them. If the voter still refuses, they become a ‘non-respondent’ and attempts should be made to re-weight the data so that this non-response effect is diminished. The catch is that the data is adjusted on the assumption that the respondents selected represented the opinion of a non-respondent on whom, by definition, we have no information. This is a big assumption that rarely gets verified. Any worthy polling company will mention non-responses and discuss how they attempt to adjust for them. Don’t trust any outfits that are not willing to discuss this!

Has the polling company asked reasonable, unambiguous questions?

If the voters are confused by the question, their answers will be too. The pollsters need to state what questions have been asked and why. Anyone can ask questions – asking the right question is one of the most important skills in polling. Pollsters should openly supply detail on what they ask and how they ask it.

How can a sample of, say, 1,000 randomly-selected voters represent the opinions of three million potential voters?

This is one of the truly remarkable aspects of random sampling. The thing to realise is that whilst this is a very small sub-sample of voters, provided they have been randomly selected, the precision of this estimate is determined by the amount of information collected, not the proportion of the total population (provided this sampling fraction is quite small e.g. 1,000 out of three million).

What is the margin of error (MOE)?

It’s a measure of precision. It measures the price paid for not taking a complete census of the data, which happens once every three years on Election Day, which we call, in statistical terms, a population result. The MOE is based on the behaviour of all similar possible poll results that could have been selected (for a given level of confidence which is usually taken to be 95%). Once we know what that behaviour is (via probability theory and suitable approximations) we can then use the data that has been collected to make inference about the population that interests us. We know that 95% of all possible poll results plus or minus their MOE include the true unknown population value. Hence, we say we are 95% confident that a poll result contains the population value.

When we see quoted a MOE of 3.1% (from random sample of n=1,000 eligible voters), how has it been calculated?

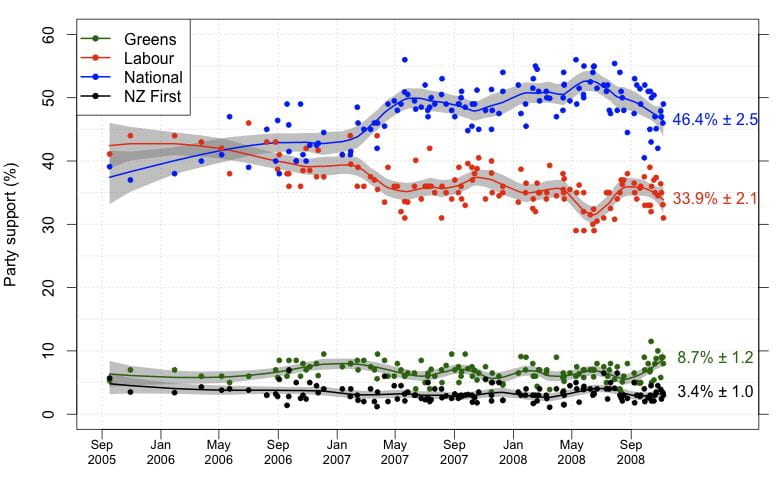

It is, in fact, the maximum margin of error that could have been obtained for any political party. It is only really valid for parties that are close to the 50% mark (National and Labour are okay here, but it is irrelevant for, say, NZ First, whose support is closer to 5%). So if Labour is quoted a having a party vote of 56%, we are 95% confident that the true population value for Labour support is anywhere between 56% plus or minus 3.1% or about 53% to 59% – in this case, indicating a majority.

Saying that a party is below the margin of error is saying it has few people supporting it, and not much else.

Its MOE will be much lower than the maximum MOE. For back-of-the-envelope calculations, the maximum MOE for a party is approximately =1/(square root of n), e.g. If n=1,000 random voters are sampled then MOE 1/(square root of 1,000) =1/31.62 =3.1%.

Comparing parties becomes somewhat more complicated.

If National are up, then no doubt Labour will be down. So to see if National has a lead on Labour, we have to adjust for this negative correlation. A rough rule of thumb for comparing parties sitting around 50% is to see if they differ by more than 2xMOE. If Labour has 43% of the party vote and National 53% (with MOE = 3.1% from n=1,000) we can see that this 10% lead is greater than 2×3.1=6.2% – indicating that we have evidence to believe that this lead of National is ‘real’, or statistically significant.

Note that any poll result only represents the opinion of those sampled at the place and time.

As a week is a long time in politics, most polls become obsolete very quickly. Note also that poll results now can affect poll results tomorrow, so these results are fluid, not fixed.

If you’re reading, watching or listening to poll results, be aware of their limitations. But note that although polls are fraught with difficulties, they remain useful. Any pollster who is open about the limitations of his or her methods is to be trusted over those who peddle certainty based on uncertain or biased information.

This article was originally published on Stats Chat and was republished with permission.

Andrew Balemi is a Professional Teaching Fellow in the Department of Statistics at the University of Auckland.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons. Reused under a creative commons license.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

Is the 2020 campaign leaving a gap for a return to dirty politics?

Who is looking the best for New Zealand’s general election?