By Rachel Simpson

The crisis of lawlessness on Facebook means it has become a breeding ground for alienation, fragmentation and xenophobia across the globe.

In a contribution to the North Carolina Law Review, Georgetown Law Professor Anupam Chander, commented on the similarities between Facebook and city or state, with a unique social infrastructure which can be seen as a replacement for traditional institutions. The social media giant is slowly taking up some of the traditional features of a society, rolling out civil safety alerts, facilitating charity donations, connecting us with politicians and public figures as well as maintaining its own marketplace where people can buy and sell. To justify all this, Facebook presents itself as an image of natural and unrestrained human organisation, hiding the fact that it is a profit-seeking corporation that relies on our data. As Facebook becomes more powerful than many nations but lacks a moral code, how can we legislate for Facebook?

The origins of Facebook are the subject of countless biographies, even a blockbuster movie, and are far from the values of “community” and “global connexity” that the platform espouses today. In 2004, somewhere inside the hallowed halls of Harvard University, a privately educated and slightly reclusive young computer programmer by the name of Mark Zuckerberg stole photos of his female classmates to set up the “FaceMash” website where Harvard students could rank fellow classmates by their physical attractiveness The campus newspaper was outraged. Zuckerberg was charged by Harvard administrators with breach of security, violating copyright, and individual privacy, but the charges were dropped. It is unknown exactly what transpired between Zuckerberg and Harvard administrators. Perhaps, like today, authorities simply had to give way to the website’s success and popularity. Within the first four hours of the website being online, people’s photos were viewed 22,000 times.

From these ethically murky beginnings, Zuckerberg built on his experiences with Facemash to develop Facebook, which is now claiming to be promoting democracy and egalitarianism. At the fundamental level, Facebook is correct that the ability to post messages to everyone without editorial control or the intervention of elected representatives is one of the most powerful democratic tools ever devised. Yet Zuckerberg, as the leader of one of the most powerful “nations” on earth, is unelected, unwilling and unsure of how to regulate it. Facebook has never had an original “social” purpose beyond making profit for its owners, and the use of the internet to manipulate our view on reality is not unique to the age of Brexit and Trump.

Having a history of legal breaches is perhaps to be expected for a company which has become an integral aspect of society. Sometimes, Facebook will tweak its policies during times of particularly bad press, such as during the aftermath of the massacre of 51 Muslim worshippers in an act of terror live streamed on the platform. However, Facebook and other technology companies receive broad immunity from responsibility for content posted on their platforms by third parties under Section 230 of the United States’ Communications Decency Act 1996, a piece of legislation which predates the digital era.

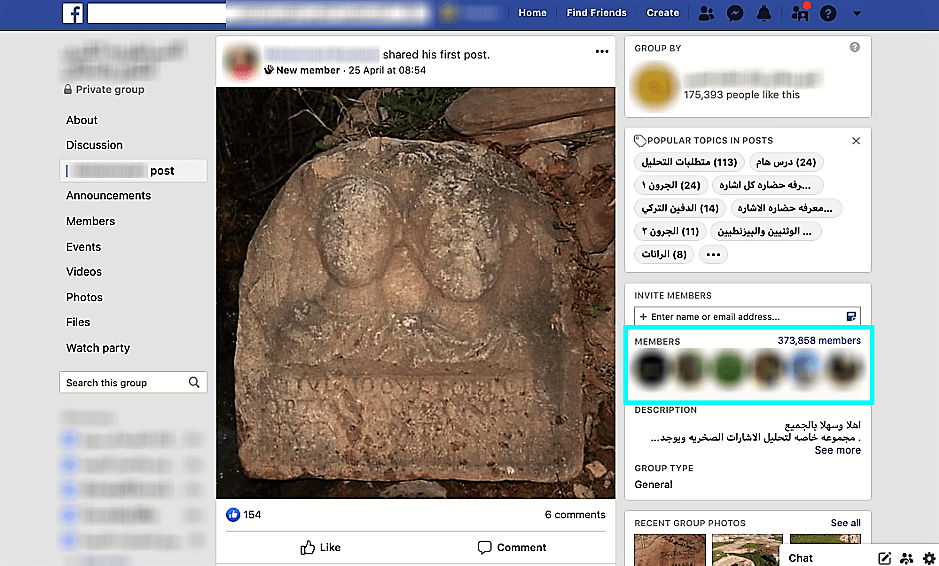

Facebook’s lack of internal policing has left a significant vacuum for transnational crime networks, and as a result, illegal activity is often able to operate in plain sight. An issue which has cropped up recently is the buying and selling of illicit antiquities from some of the world’s most conflict-ridden areas, with items such as ancient artefacts, wildlife parts and even human remains being bought and sold on Facebook marketplace. No special skills are required to access these illegal groups, but the people involved range from average people digging up artefacts to sustain themselves, terrorist organisations, crime rings, and white collar buyers. When the New York Times picked up on this illegal trade, Facebook said it would commit to banning such groups that “violate community standards.” But if the pages are not reported to authorities, and nothing in their community standards mentions illicit cultural property, then they are allowed to remain open for business.

[Caption – A user listed in Oran, Algeria posts an image of a Roman relief laying in a field in a Facebook group for antiquities looting and trafficking with more than 373,000 members — the largest of the more than 120 Facebook black market groups monitored by the ATHAR Project. (Screen capture taken on April 30, 2020). Source: ATHAR Project / Facebook]

How do we make the rules for a website that presides over such a vast swathe of humanity? Facebook circulates its own currency, has its own diplomats, and even holds a kind of taxing power through its sharing of the revenues garnered via commerce on its site. It holds enormous influence, yet the field of cyberlaw is still constantly running into foundational issues. If allowing Facebook’s management free reign to self-regulate hasn’t been effective, the question of who should legislate for Facebook becomes prominent. A United Nations treaty, given the international body’s existing inability to even collect outstanding fees from member nations, would be largely illusory. Letting Facebook’s home country, the United States, be the exclusive regulator would be efficient, but would cause conflict with foundational ideas of international law. The remaining options are letting home countries of users regulate, or letting the users regulate Facebook themselves. As New Zealand Prime Jacinda Ardern said, however: “Ultimately, we can all promote good rules locally, but these platforms are global.”

The crisis of lawlessness on Facebook means it has become a breeding ground for alienation, fragmentation and xenophobia across the globe. If social media is to play such a key role in society, a place for political organisation and an alternative to existing governments, it must depart from its history as an unregulated market mechanism. The nation of Facebook needs laws like anywhere else.

Rachel Simpson is a second-year law student at the University of Auckland, as well as a news and current affairs broadcaster at 95bFM radio in Auckland.

A variation of this piece first appeared on the Equal Justice Project. For the original, click here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

Taking issue: Is social media good or bad for democracy?

Facebook isn’t cool anymore: What killed it?