By Stefano Riela

The lockdown, introduced at the beginning of March to contain the spread of Covid-19, has been an economic nightmare for the country.

In the last weeks Venice has been unusually quiet even in its canals, now revealing a multichromatic sea life. That is the perfect location for the romantic loneliness we have dreamt of while immersed in our pre-lockdown polluted and noisy routines. However, the lockdown, introduced at the beginning of March to contain the spread of Covid-19, has been an economic nightmare for Venice as for the rest of the country.

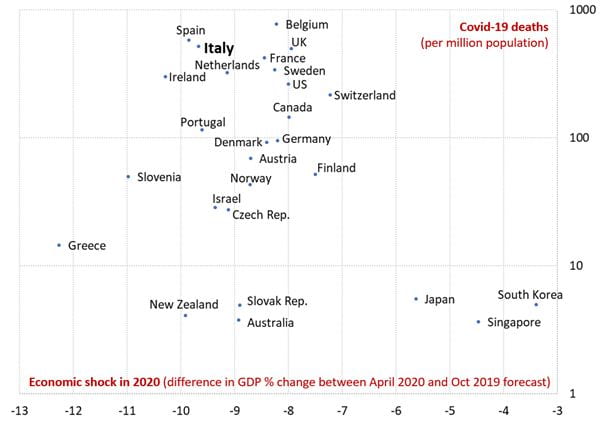

According to the IMF (April 2020), in 2020, the Italian GDP will shrink by 9.1% compared to 2019; by comparing this figure with the +0.5% for 2020 forecasted in October 2019, we obtain an economic shock equal to -9.6% in the horizontal axis of the graph. That is not the worst performance among the developed countries if we consider that for many days, Italy has led in the unfortunate ranking of Covid-19 infections and deaths. For example, the forecasted economic shocks in New Zealand and in Ireland are larger, respectively -9.9% and -10.3%.

The size of the economic shock is the result of the stringency and length of lockdown measures, with negative impact on both supply and demand, and of degree of economic integration of the country with other countries affected by Covid-19. Ceteris paribus, the higher the international exposure of a country, the worse its probable economic shock: this is generally the case of countries whose goods and services (such as education and tourism) sold abroad represent a relatively high share of the GDP.

The Italian exception attracted international media attention due to its Covid-19 absolute figures of infections and deaths. Some explained it with demographics (Italy is one of the ‘oldest’ country in the world) and with the insufficient preparedness of the health system (in particular with Intensive Care Unit beds) to cope with the unexpected increase in infections.

But the truth is that after several weeks of pandemic, epidemiologists are still scratching their heads over why the virus had such a diverse geographical impact: severely hitting some countries while leaving neighbors relatively untouched. This heterogeneity is clear in the graph that shows, in the vertical axis, the deaths to the population (as of 15 May) in a log scale. Moreover, according to this ratio, Italy is not leading the unfortunate ranking anymore. However, those figures do not fit the purpose of international comparison due, in primis, to differences in testing capacity and public health protocols: first, there could be differences in identifying the cause of death in Covid-19 patients with underlying conditions; second, some countries count only those who die in hospitals (e.g. the UK), others include those who die outside hospitals (e.g. Italy) and also those suspected of carrying the virus who were never tested (e.g. Belgium).

Now, with the decline of the new Covid-19 infections in Italy, the government has loosened the lockdown to let the economy restart in different phases according to a decreasing level of essentiality. However, safety measures should be implemented, for example, with restaurants required to set distances of four meters between diners.

As in every country of the Northern Hemisphere that has entered into a declining trend of infections, the aim is to revamp the respective economies getting ready for the summer holidays.

On 13 May, the European Commission presented a package of guidelines and recommendations to help Member States gradually lift travel restrictions and allow tourism businesses to reopen. Unfortunately, due to the epidemiological differences between countries, the Commission has proposed a phased approach that starts by lifting restrictions between countries with sufficiently similar health situations. Though this cautious approach reduces the risk of a second wave of Covid-19 infections, it might create a two-speed Europe; privileged touristic paths based on quarantine-free travel bubbles might exclude those Mediterranean countries that have experienced higher mortality rates such as Italy. This can further worsen the plummeted disposable income of the Italians also due to the limited fiscal room for manoeuvre of the government; the Italian sovereign debt, in fact, reached 135% of the GDP in 2019 (the highest in the EU after Greece) and the financial help from the EU has been – quantitatively and qualitatively – constrained by unaligned understandings of solidarity.

For more information on COVID-19, head to the Ministry of Health website.

Stefano Riela is a research fellow at the Europe Institute, University of Auckland. Stefano is an expert in European integration and EU trade policy.

This article is published as part of a series commissioned by the Europe Institute at the University of Auckland.

For more on the Europe Institute click here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like: