By Kate MacKrill

Kate Mackrill explores what is known as the nocebo effect and whether the media can, in fact, influence the side effects of medication.

You are probably aware of the placebo effect – a therapeutic benefit from a sugar pill or even real medication simply because the person believes in its efficacy. But have you heard of its ‘evil twin’, the nocebo effect? This is the negative reaction or side effects from a medicine brought about by a person’s expectations, rather than the actual drug. The nocebo effect is very common. Research shows that in clinical trials that test the effect of a real medicine against a placebo tablet, almost 50% of participants in the placebo group will experience side effects. In fact, it has been estimated that 70-80% of the side effects attributed to a real medicine are not actually from the drug but due to the nocebo effect.

The nocebo effect occurs through the interaction of expectations and attention. When people are warned of the potential side effects from a medicine, they come to expect those side effects so pay more attention to their body and physical sensations. This increases the likelihood of noticing normal symptoms, like headaches or tiredness, and naturally assuming that they are caused by the medication. Negative expectations can also come about through seeing or hearing about other people’s reactions to a drug. One study showed that when female participants observed someone else report side effects, they attributed more symptoms to a placebo tablet than those who did not. While this was an experimental demonstration, in the ‘real world’ we are frequently exposed to other people’s experiences through the media.

An example of this occurred on February 28, 2018, when the New Zealand Herald published an article titled ‘Patients say generic Pharmac-funded version of antidepressant left them depressed, anxious’. On the same day the Stuff website released the online article ‘Antidepressant swap: sufferers claim generic drug is harming their condition’. These articles reported on a small group of patients who had an adverse response following a change in the funded brand of the antidepressant medicine, venlafaxine.

Up until 2017, 45,000 New Zealanders were prescribed either Pfizer’s original brand of venlafaxine, Efexor XR, or a generic called Arrow-Venlafaxine XR. Following a competitive tender process, Pharmac solely funded another generic venlafaxine, Enlafax XR from Mylan. All three medicines contain the same active ingredient, venlafaxine, and had been approved by Medsafe, the medicines safety authority, so have the same efficacy, safety and side effects. A few months later on April 29, Stuff released another article, ‘Fight over Pharmac’s switch to generic anti-depressant continues’, which carried on the discussion about patients’ negative experiences with Enlafax.

As part of my research, I looked at the effect of the media on side effect reporting following the venlafaxine brand change. Using data from the Centre for Adverse Reactions Monitoring (CARM), my colleagues and I analysed changes in the number of side effects reported each month and reports of reduced drug efficacy before and after the media coverage. We looked at changes in the reporting rate of side effects specifically mentioned in the media and compared them to other side effects that were not mentioned in the media stories.

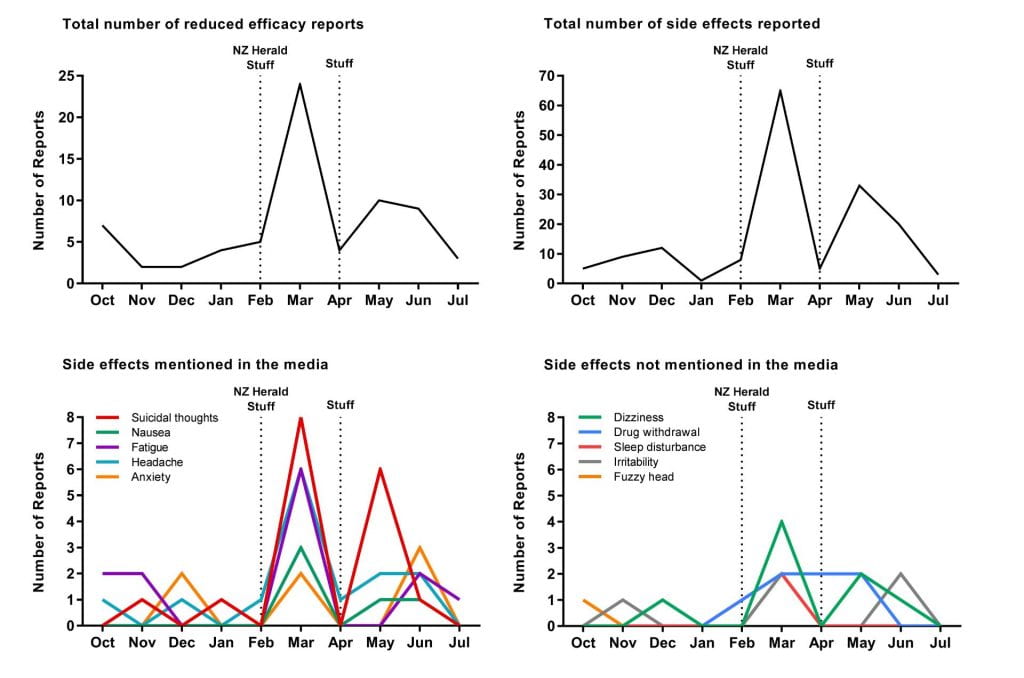

Overall, we found a clear association between the timing of the media articles and spikes in the frequency of adverse reaction reports to CARM. In the five months prior to the first media article, there was an average of 6 adverse reaction reports to CARM per month. After the publication of the two February articles, this jumped to 34 reports in March – an increase in the reporting rate by 467%. Adverse reaction reports returned to the average in April but rose again in May to 17, which corresponded with the release of the second Stuff article at the end of April.

We examined the content of these adverse reaction reports and found a similar pattern for complaints of reduced drug efficacy, which increased from a pre-media average of 4 reports per month to 25 in March. As the graphs below show, there was also a considerable increase in the total number of side effects reported to CARM, increasing from an average of 7 side effects per month before the media focus to a total of 65 in March and 33 in May. We found that it was largely the side effects that were mentioned in the media that increased in the months directly after the coverage, with reports of suicidal thoughts having the greatest increase. The reporting rates of side effects that were not mentioned by the media did not change significantly.

A series of graphs showing the number of reports of reduced drug efficacy and side effects, before and after the media coverage (October 2017 to July 2018).

So what is going on here? The most likely explanation is that the media coverage of the venlafaxine brand change has influenced patients’ expectations about the experience of side effects from the newly funded generic, Enlafax, resulting in greater reporting. We can discount the fact that the media stories just drew patients’ attention to CARM as a means to register their experience as the side effects mentioned in the media stories were subsequently reported at greater levels than those not mentioned.

An important influencing factor is that up to a third of people have negative views of generic medicines and medicine brand changes. In an illustration of this, a recent study found that patients experience fewer side effects and have greater pain relief from brand-name tramadol but experienced the opposite effect when the same medication is made to look like a generic. Furthermore, when participants were changed from one brand of beta-blocker to another (in reality they were both placebos) they reported more side effects and experienced a smaller reduction in blood pressure and anxiety from the new tablet compared to the original.

How could we avoid similar increases in side effects from media stories in the future? One important strategy may be for the media to acknowledge the number of people who did not experience side effects from the medicine in question. Another approach could be to provide information on the nocebo effect, as this knowledge may be reassuring for some people and help ‘inoculate’ people against a nocebo reaction. There is some research showing that this may work. It is important to note that suggesting side effects might be due to the nocebo effect does not imply that they are “all in the person’s head”. The symptoms are real but they may not necessarily be caused by the medication. We accept that the placebo effect is responsible for some of the therapeutic benefit of a medicine; equally we should be aware that some of the side effects could be due to the nocebo effect.

Kate MacKrill is a Ph.D. Candidate in Health Psychology at the University of Auckland.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

The opioid crisis: fact vs. fiction

What is a hallucinogen? What these mind-altering drugs do in our brains