By Niklas Bolin, Kajsa Falasca, Marie Grusell, Lars Nord

In the wake of the European Elections in May 2019, seventy leading academics from across the European Union contributed their reflections, thoughts, and analysis to Euroflections – a free downloadable report compiled by the research centre DEMICOM at Mid Sweden University.

Migration, Brexit and Trump. There is no doubt that recent years have been extremely turbulent and challenging for the European Union. Consequently, the European election campaign context in 2019 was very different from the previous one five years ago.

In the autumn of 2015 the huge migration flows from the Middle East and Africa to Europe took many EU leaders by great surprise, and showed that hitherto commonly agreed principles to handle such situation were not possible to implement. Member states were deeply split on effective immigration policies, and the polarised positions on this issue have remained as an important political controversy within the union.

Then followed Brexit. What few in Europe believed could happen actually happened. After the UK referendum in June 2016, Britain decided to leave the European Union. As one of the most important member states and net economic contributors to the union, Britain’s decision will have a huge impact on EU affairs in the forthcoming years. It is also important to note that the Brexit process and the chaos that followed this decision appears to have silenced EU sceptical parties in other member states, at least when it comes to the debate about remaining in the union or not.

The third surprise was Donald Trump. His unexpected victory in the US presidential election in November 2016 caused new tensions between EU and the US. The ‘America first’-vision of Trump resulted in foreign policy shifts and new international trade actions that are definitely not in the interests of the European Union.

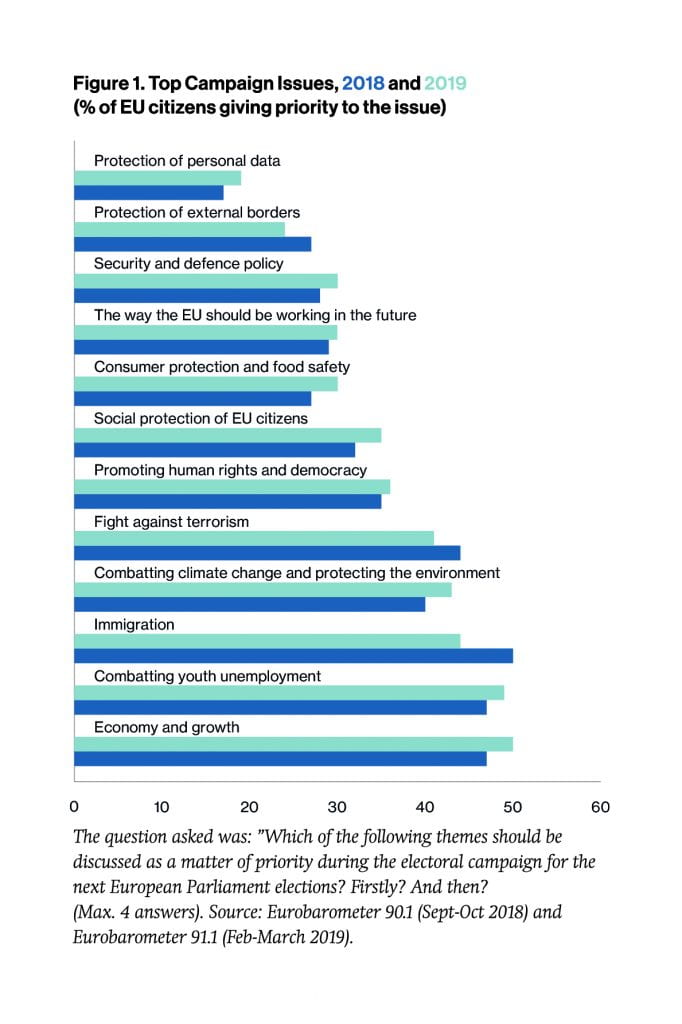

However, it seems like these surprising and dramatic events have had limited influence on the political agenda when EU citizens were asked to name their priority political issues a few months before the European Elections 2019. In the very beginning of the campaign, the highest ranked issues among voters were economy and growth, and the fight against youth unemployment. Climate change was also ranked higher than in previous surveys, while immigration was ranked lower than before. EU as a political organisation may be perceived as weaker and more divided than before, but EU citizens still believe the union is able to play an important role in improving economic conditions and handling urgent transnational issues.

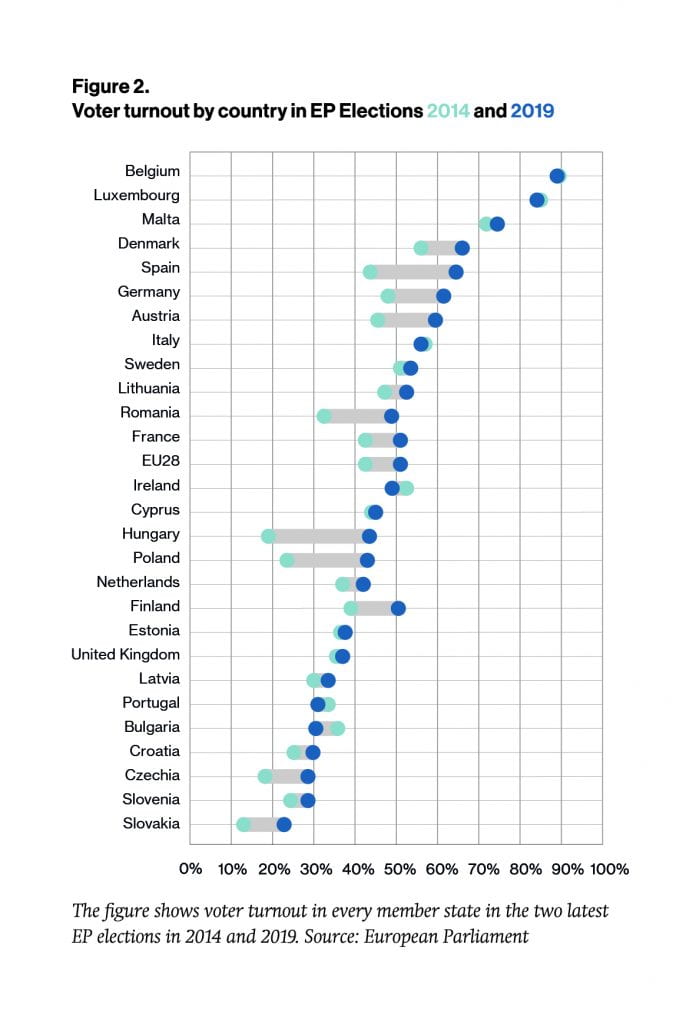

The Eurobarometer in Spring 2019 also showed that 68 per cent of EU citizens believe that EU membership is good for member states, and 61 per cent say that membership is a good for their own country. This figure has not been as high since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the communist bloc in Eastern Europe in 1989. A narrow majority of EU citizens also voted in the European elections 2019. Voter turnout increased in 20 of the 28 member states. The common wisdom that EU citizens think there is ‘less at stake’ in EP elections may be false. On the contrary, it is plausible to believe that more voters than before – and particularly younger generations – share the opinion that important political issues do not recognise national borders and need to be addressed on the international level. The significant average increase in voter turnout in EU28 was definitely a success, even if figures are still modest compared to most national elections on the European continent.

At the same time, the higher level of political participation and voter interest in EU issues probably need to be interpreted cautiously. In fact, many European elections campaigns in 2019 were highly influenced by domestic political agendas and existing conflict dimensions on the national level. Mobilisation of voters for the European election was therefore often based on arguments not relevant for EU political affairs, and more associated with the national political agenda.

Against this background, votes in the European elections may be basically perceived as reflections of current national public opinion. In terms of the party political landscape, much of the pre-election speculations dealt with assessments about how much ground Eurosceptic forces would gain at the expense of the old dominant pro-European party groups.

Both of the biggest groups EPP and S&D were predicted to lose. Similarly, many expected the election to be a continued surge of the Eurosceptic populists. The result, indeed, reasserted the prognosis. However, while the general picture is in line with expectations, we do not need to dig deep before a slightly different picture emerges. A look beneath the aggregated numbers reveal quite a number of exceptions from the overall trend.

While the EPP and S&D lost quite heavily, both groups include winners. Fidesz led by the controversial Hungarian Prime Minster Viktor Orban, and at the time of the election a suspended member of EPP, was one of only two parties (the other one was the Malta Labour Party) that managed to win more than a majority of its country’s votes. Despite turbulence at the domestic arena the Austrian ÖVP also gained electoral support. A third example of a successful member of the EPP is the resurgence of the once dominant Greek New Democracy. In Spain the socialist PSOE, reinforced by its recent domestic electoral success, did exceptionally well. The Dutch counterpart PvdA, one of often cited examples of the general social democratic decline in Europe, surprised many and became the country’s biggest party.

While the EPP and S&D lost quite heavily, both groups include winners. Fidesz led by the controversial Hungarian Prime Minster Viktor Orban, and at the time of the election a suspended member of EPP, was one of only two parties (the other one was the Malta Labour Party) that managed to win more than a majority of its country’s votes. Despite turbulence at the domestic arena the Austrian ÖVP also gained electoral support. A third example of a successful member of the EPP is the resurgence of the once dominant Greek New Democracy. In Spain the socialist PSOE, reinforced by its recent domestic electoral success, did exceptionally well. The Dutch counterpart PvdA, one of often cited examples of the general social democratic decline in Europe, surprised many and became the country’s biggest party.

In total, Eurosceptic populists, made marked gains. In Italy, Lega became the biggest party. In France Le Pen’s National Rally managed to beat Macron’s Renaissance and in Britain the newly formed Brexit Party at the helm of Nigel Farage, won more than one in four votes, just to name a few examples. However, at the same time, the left-wing radical parties of the GUE/NGL group are among the biggest losers. In the wake of the Eurozone crisis, parties like the Spanish Podemos, the German Die Linke and the Greek Syriza made an impact in the polls in 2014. After the 2019 election they find themselves being the smallest group.

Also among the right-wing populists there are important instances going against the overall trend. Wilder’s Freedom party loss all their Dutch seats and the Danish People’s Party lost three out of five votes becoming only the fourth biggest party in Denmark. Next to the scattered group of Eurosceptic populist to the right, two other groups can be coined the winners of the election. Including the seats of the new Renaissance coalition led by French president Macron’s En Marche and the temporary seats of the British Liberal Democrats, the ALDE&R group increase its seat share with more than 50 per cent.

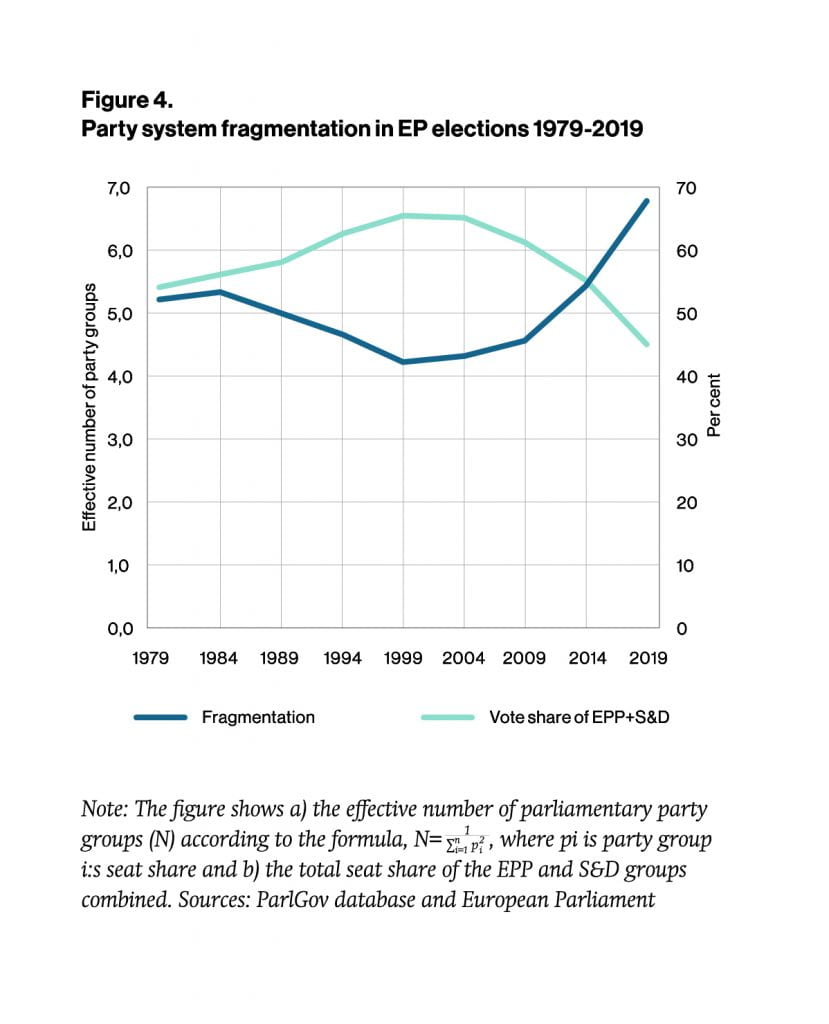

Also the The Green/EFA group made big gains. These groups electoral progress arguably is an important counterweight against those who wish to coin the elections a victory of the Eurosceptics. The overall picture that emerges is one of complexity. The big party groups are getting smaller. The small party groups are getting bigger. Never before have we faced such a fragmented European parliament. Both of the big groups lost almost 20 per cent of their seats each, leaving their combined seat share short of a majority for the first time ever.

This is of course a major incident. No longer can the two dominant driving forces of European integration, by themselves, make decisions without the consent of at least one other party group. While the European parliament surely is a bastion of negotiations and pragmatism, this situation is new and means we might enter a phase of adaptation before these party groups have settled with the new playing field. At the same time the electoral success of the Eurosceptic right-wing populists will not automatically be translated into political influence.

While their overall strength has increased, parties to the right with critical stances towards the EU are divided among many different groups. We also know from the past that these parties have had problems of finding a way to cooperate both within and across party groups. It remains to be seen if they will be able to improve on their rather lacklustre previous performance on this account. While parties such as Lega, the Brexit Party and Fidesz might have somewhat similar ideas about the shortcomings of the EU, they surely differ as much as they have in common on most other issues dealt with by the European parliament. With increased strength, the pro-European liberal and green groups are certainly also other forces who will do as much as possible to keep the Eurosceptics away from influence.

So what are the major take away points of the European elections 2019?

Although Eurosceptical parties have won a greater share of seats than ever before, there are also positive signs from an EU perspective. Although the turnout is far below a decent level, the trend is upwards. The overall attitudes towards the EU seems to be on the rise. Brexit seems to have made both citizens and parties less prone to demand an exit from the union. However, even though there are some positive signs for those who embrace the idea of a continued strong union, there are at the same time important indications that speak against the wishes of those that harbour ideas about more supranationalism. The campaigns were predominately national. Despite attempts to make it a real European election – think for instance about spitzenkandidaten, joint party group manifestos and suggestions about supra-national seats – few voters seem to regard the election as a European vote. Instead national factors such as different regulations and the persistence of various political cultures and traditions have a great influence on the forms and content of the campaign in the different nations.

Voters around Europe were exposed to quite different campaigns dependent on where they live. Moreover, despite the ongoing evolution of the media, there still is no real influential single European media market. And while the elections indeed have winners and losers at the aggregate level, an in-depth analysis reveal that the picture is much more scattered. In most party groups, we find big winners and big losers. If anything, the campaign and the results suggest that domestic issues, events and parties still are more important than what happens at the European level. While this might please some and disappoint others, the overall judgement is clear. We should not think of the recently completed election as one major European event as much as 28 different national events merely collected by name under a pan-European umbrella.

This text was originally published in the edited volume Euroflections: Leading academics on the European elections 2019, a free downloadable report with results, analyses and reflections on the election to the European Parliament 2019. More than 70 researchers from all over Europe participate in the project led by the editors Niklas Bolin, Kajsa Falasca, Marie Grusell and Lars Nord. Download the report and read more about the project here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this discussion reflect the views of the participants and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like: