By Helen Jiang

The Global Anticorruption Blog’s Helen Jiang explores whether scandalising political corruption in the news media can backfire.

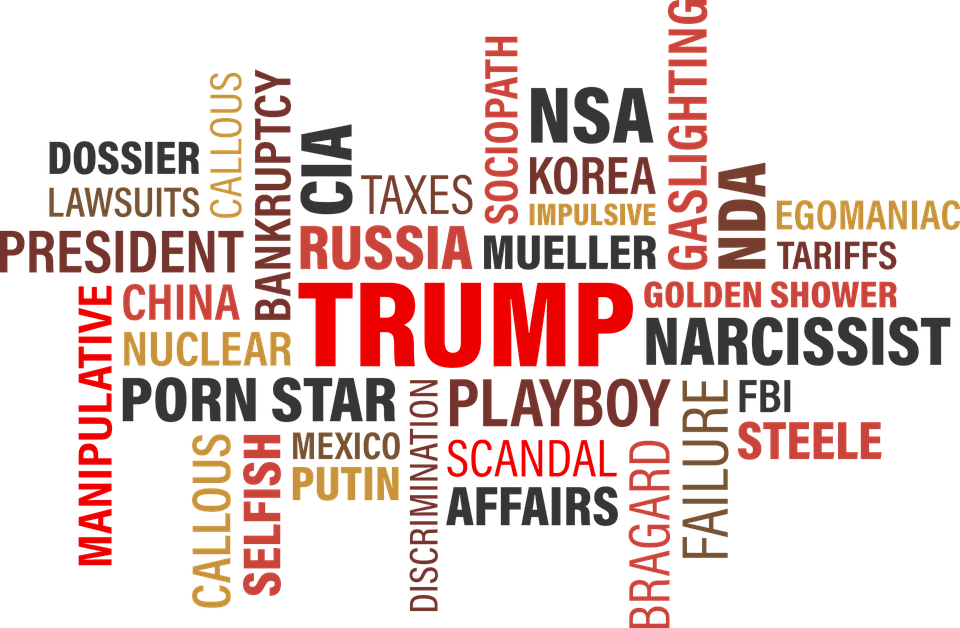

High profile corruption scandals are making headlines almost every day: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is embroiled in multiple bribery allegations; Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known as Lula) was convicted for his involvement in corruption; Peruvian President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski was forced to resign after his allies were caught on tape buying political support to defeat his impeachment vote. The list could go on and on. And one cannot help noticing that the media coverage of these high-profile corruption cases often focuses on the most lurid, sensational aspects of individual politicians’ corrupt behavior. For example, as the Netanyahu probes unfolded, the Israeli media emphasized the juicy details: how Netanyahu and his wife were bribed with Cuban cigars and Dom Pérignon worth up to $130,000, the state’s annual allocation of approximately $3,000 for the PM’s pistachio ice cream supply, and his son’s bragging of how his father pushed through a gas deal caught on tape in a strip club. And this is but one example. It seems that corruption cases are often covered as if they were TV dramas, with entertaining plot twists and voyeuristic appeal. To put this in the terminology developed by Shanto Iyengar in his book on how TV news frames political issues, much of the contemporary media coverage of corruption tends to be “episodic” (focusing on individual stories or specific events, putting the issues in a more subjective light, and including sensational or provocative content) as opposed to “thematic” (more systematic, abstract, and in-depth, and providing a wider context for a more nuanced understanding of the causes and trends).

Such salacious coverage of corruption is perhaps unavoidable; these tawdry details attract more readers and viewers than dry reporting on financial misdeeds and back-room negotiations. And one might think that such coverage would be more effective in motivating citizens to take action against corruption—whether through votes, protests, organizing, or other means. After all, as Jimmy Chalk argued last year on this blog, anticorruption narratives can be more effective when they include dramatic stories with virtuous heroes and sinister villains. That may well be true for narratives fashioned by activists in the context of a campaign, but for news reporting, the episodic/scandal-centric approach may be counterproductive, for three main reasons:

- First, the focus on corruption cases as lurid personal scandals threatens to trivialize corruption, transforming a deeply-rooted social problem into a source of voyeuristic entertainment—with the public perhaps feeling disgust and righteous indignation, but not provoked or invited to think about the bigger questions of systematic corruption or how to reform institutions to address those underlying problems. Scandal-focused coverage of corruption sends the message that naming, shaming, and taking down individual corrupt politicians is the way to eliminate corruption in the system, obscuring corruption’s deeper structural causes. Moreover, while the corruption scandal itself may be covered in-depth, the aftermath of the scandal typically isn’t, what with the fast pace of the political news cycle. The public should not only be informed that a scandal has occurred, but need to understand the systemic, institutional, and legal failures that produced or enabled the bad behavior, and what can be done about this. Otherwise, even if scandal-focused reporting raises awareness, this increased public attention will not contribute to actually fixing the underlying problems.

- Second, media focus on the more salacious, outrageous aspects of corruption scandals involving individual politicians may overshadow or obscure the incremental improvements that have been achieved law enforcement agencies, civil society groups, and other related institutions. These stories deserve to be featured in media headlines as much, if not more, than the scandals. Fixing systemic corruption problems cannot happen overnight, but requires long term efforts, with many obstacles and setbacks. Achieving real progress is a “two steps forward, one step back” kind of process, and continuous public attention and positive encouragement is essential. If the media paid more attention to the progress that is being made, rather than just dwelling on ostentatious bad behavior by corrupt actors, this could generate positive feedback loops and mobilize wider public engagement in fighting corruption. This possibility is lost when corruption scandals steal all the limelight.

- Third, while reporting on corruption scandals can of course damage the reputations of the politicians who are the subjects of these stories, the episodic/scandal-focused approach to corruption coverage can also damage the media’s own credibility. This risk is especially acute when the public already distrusts the media, and where the media has a reputation for partisanship. In such an environment, media coverage that appears overly personal can be spun by the targets as an unfair, biased media vendetta, confirming in the mind of a skeptical public that media outlets are “scandalmongers” with their own agenda. This, in turn, can perversely strengthen the position of the politician who is the subject of the salacious reporting. In Israel, this seems to have occurred with Netanyahu, for example.

Of course, none of this is to say that the media should stop exposing political corruption scandals. The public has a right to know when politicians are abusing the public trust to enrich themselves, and vivid narratives may be more effective in engaging public attention than dry statistics. Yet the media should aim to do more than merely drum up public outrage. Attention to individual scandals can get people’s attention, but when the media fixates excessively on the salacious details of individual corruption scandals, without placing these events in larger context, the end result can be counterproductive.

This article was originally published on the Global Anticorruption Blog and was republished with permission. For the original, click here.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

What needs to be done to solve the fake news crisis? Is Trumpism the end of globalism? 🔊

Are hacking, fake news, and paid trolls destroying democracy? 🔊