By James Oleson

Criminologist James Oleson looks into the controversial three strikes law in New Zealand and whether it works as a policy in keeping communities safe.

After announcing in 2017 that New Zealand’s controversial three-strikes law would be repealed,[1] Justice Minister Andrew Little was forced this month to abandon his plan. Without the support of New Zealand First, the coalition government simply did not have the requisite votes to end three-strikes.[2] Repeal of the law might still take place as part of a raft of larger criminal justice reforms,[3] but for the present, three-strikes remains good law in the Land of the Long White Cloud.

Recidivist offender laws are nothing new. Laws that increased penalties for repeat offenders can be traced back to sixteenth century England and colonial America.[4] In New Zealand, laws of this kind are more than one hundred years old: the Habitual Criminals Act 1906 authorised the indefinite detention of offenders with two or more qualifying crimes.[5] But after decades of disuse, three-strikes legislation of this kind was rediscovered, reinvigorated, and redeployed in the last twenty-five years.

The task of the sentencing judge is enormous. It is sometimes described as the most difficult thing a judge ever has to do.[6] In determining an appropriate sentence, New Zealand judges are instructed to weigh the totality of the evidence in light of ten competing considerations.[7] Criminal sentences are intended to serve multiple purposes,[8] but four cornerstones are frequently emphasised:

- Deterrence: If an offender commits a crime and is punished for it, that offender will be less likely to reoffend. Furthermore, because people learn vicariously, a punishment imposed upon one offender will deter others from committing the crime.

- Incapacitation: Some forms of punishment (like probation or prison or capital punishment) make it difficult or impossible for an offender to reoffend.

- Rehabilitation: If crime occurs because of defects (psychological, moral, social, etc), future crime can be prevented by correcting the defect.

- Retribution (aka Just Deserts): Differs from the three other (utilitarian) bases of punishment, arguing that criminals should be punished because they deserve it, regardless of prospective consequences: “Fiat justitia ruat caelum” (May justice be done though the heavens fall). Retribution redresses the unfair advantage of society that the criminal has taken.

The underlying logic of three-strikes legislation is that failures in deterrence can be compensated via increases in incapacitation. That is a lawyerly way of saying that if an offender does not learn his lesson after being punished and goes on to reoffend – and in New Zealand, as in other jurisdictions,[9] many released prisoners do reoffend, 49% of those coming out of prison will return to prison within four years[10] – then the second punishment should be greater, increasing the ‘price’ of crime; if the offender does not learn from the second punishment, then the third should be greater still.

Although incremental sentencing conceals underlying jurisprudential puzzles (eg, exactly how does increasing penalties on the basis of previous convictions not violate the Bill of Rights Act’s prohibition against double jeopardy?),[11] it is a practical, sensible logic, especially since research suggests a small fraction of the population is responsible for a disproportionate volume of crime.[12]

The New Zealand three-strikes law that was enacted in 2010 was modelled upon California’s 1994 three-strikes law. The California law, created in response to a couple of high-profile murders of young women, had a number of unusually draconian provisions:[13]

- Many qualifiers: The three-strikes law could be triggered by 21 different violent crimes (including many forms of assault and, curiously, burglary) and 42 serious crimes (including providing some forms of illegal drugs to minors)

- Second strikes: If a person had one previous serious or violent conviction, the sentence for any new felony (not just serious or violent ones) was twice the term otherwise required under law

- Broad third strike eligibility: Any felony could count as a third strike. If a person had two or more previous serious or violent felony convictions as predicates, any new felony conviction (not just serious or violent ones) was life imprisonment with the minimum term being 25 years

- Stacking: The statute required consecutive, rather than concurrent, sentencing for multiple offenses committed by strikers. For example, an offender convicted of two third-strike offences would receive a minimum term of 50 years to life. There was no limit to the number of felonies that could be stacked

- No diversion: Probation, suspension, or diversion could not be granted for new crimes, nor could imposition of the sentence be suspended for any prior offence. The defendant had to be committed to state prison and was not eligible for diversion

- Reduced good time: Most California prisoners can reduce their sentence by as much as one-half by earning “good time” credit through education or work, but strikers are restricted: at most, they can reduce their sentence by one-fifth

For these reasons, the California three-strikes law was denounced as “the toughest law in America.” In 2003, for example, at least 360 people were serving life sentences for shoplifting.[14] By casting a wide net, with many qualifying offences, imposing very long sentences (25 years to life for each third strike) with no real mechanisms for sentence reductions – no diversion and restricted good time – the three-strikes law expanded the California prison population. It is basic physics: if you fill a balloon with more water than you take out, the balloon will fill. Eventually, it will burst. And that is what happened with the California prison system.

In 2011, the United States Supreme Court decided Brown v. Plata,[15] and found that California’s prisons were so crowded that “an inmate in one of California’s prisons needlessly dies every six to seven days due to constitutional deficiencies in the medical delivery system.” Three-strikes was not the only cause of California’s prison crowding, but it was a cause. California was ordered to reduce its prison population by 46,000 people within two years. However, instead of releasing non-violent offenders (believed to be tantamount to career suicide for elected prosecutors and lawmakers), state officials pursued a policy of “justice realignment,” by simply transferring low-risk prisoners from state prisons (where they would be counted) into local jails and private prisons (where they would not be).

One year after Brown v. Plata, Californians passed a new voter initiative – Proposition 36 – that ameliorated some of the excesses of three-strikes. It limited imposition of a third strike to enumerated serious or violent felonies – this prevented cases such as the defendant who was sentenced to 25 years for stealing a slice of pizza[16] – and it allowed third-strike prisoners who were not convicted for a serious or violent felony to petition the court for a reduced sentence. Sentence reduction is not automatic, however: in 2017, the California Supreme Court held that a subsequent voter initiative, limiting the issues that judges may consider when deciding whether public safety warrants sentence reduction, does not apply to three-strikes cases.[17]

Some researchers report that three-strikes laws produce significant reductions in crime. Shepherd reported deterrent effects on murder, assault, robbery and burglary.[18] Ramirez and Crano reported that three-strikes reduced instrumental crimes by 45%, violent crimes by 36% and minor crimes by 34%.[19] Helland and Tabarrok estimated that threat of a third strike reduced felonies among those with two prior strikes by 20%,[20] and Chen reported a modest deterrent effect for robbery, burglary, theft and motor vehicle theft.[21] Other researchers, however, have concluded that three-strikes’ impact on crime is modest, even counterproductive. After controlling for county-level effects, Worrall concluded that three-strikes had no effect on crime,[22] and Marvell and Moody reported that three-strikes exerted a negative deterrent effect on murder at strike three, suggesting that offenders with nothing to lose may kill to avoid apprehension.[23]

It is hard to estimate the deterrent and incapacitative effects of the New Zealand three-strikes law, since this law is far less rigid and far less punitive than the California legislation upon which it was modelled.[24] Like the California law, the New Zealand law imposes escalating sentences at the first, second, and third strike. Like the California law, the first non-murder strike in New Zealand is nominal and does not affect the sentence imposed. However, unlike the California law, which doubles the usual sentence at strike two, the New Zealand law simply requires that the offender must serve the entire sentence specified by the judge (whatever that is), without parole. And whereas the California law imposes a mandatory 25-to-life sentence for each third-strike offence, regardless of the crime committed, the New Zealand law simply imposes the maximum penalty authorised by law – allowing the judge to impose a lesser sentence only if the failure to do so would result in “manifest injustice.” This manifest-injustice provision operates as a safety valve that is not available in California, where judges, Pilate-like, were forced to impose sentences they knew to be wrong. Thus, the New Zealand three-strikes scheme is less rigid and less substantively punitive than the California law.

This has obvious advantages: it reduces the risk of egregious miscarriages of justice,[25] and slows (relatively) the expansion of the prison population, but it also reduces the certainty of punishment at strikes two and three, undermining its value as a deterrent. And because the longest prison sentence available under the New Zealand law is the statutory maximum (without parole) – not 25 years to life – the incapacitative effects of the law are limited.

California’s three-strikes law disparately impacts minorities. In 2013, African Americans constituted only 6.6% of the state population, 28% of the prison population, but 33.5% of all second-strike and 45.7% of all third-strike California prisoners. On the other hand, non-Hispanic whites made up 39.4% of the state population but only 24.1% of strikers.

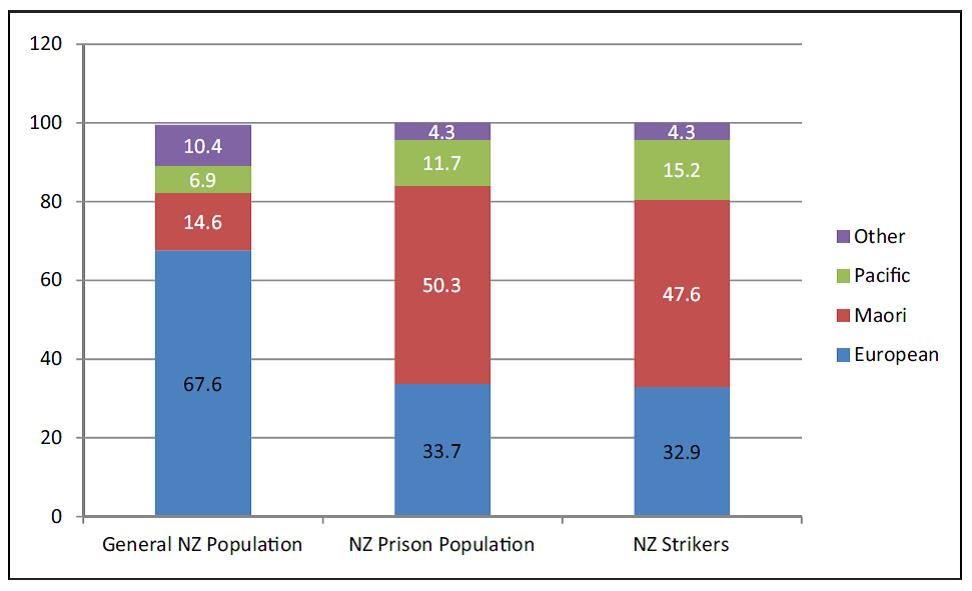

In New Zealand, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that the ethnic composition of strikers is roughly equivalent to the ethnic composition of prisoners. Given that three-strikes is intended to incapacitate incorrigibles, the worst-of-the-worst, the striker population should look like prison population. This is the silver lining on a storm cloud. The bad news is that the ethnic composition of New Zealand prisons is grossly distorted. While Māori constituted about 14.6% of the New Zealand in 2013, they constituted 50.3% of the prison population and 47.6% of the striker population. Pasifika constituted 6.9% of the New Zealand population, but 11.7% of prisoners and 15.2% of strikers.

A recent poll conducted by victims-rights group, the Sensible Sentencing Trust, found robust support for the New Zealand three-strikes law: of the 965 adults polled, 68% approved of the law, 20% disapproved, and 12% were unsure or declined to answer.[26] But judges hate the law.[27] Criminologists hate the law.[28]

One size-fits-all-punishment is both wasteful and expensive: $100,000 NZD per year of incarceration. It discourages judges – who already have the ability to ensure public safety under existing sentencing laws, including preventive detention – from applying the full spectrum of sentencing considerations.[29]

In the first third-strike case to reach New Zealand’s courts, Justice Kit Toogood echoed the sentiments of other judges, from other jurisdictions, who in the past have been constrained by bad laws.[30] He told the defendant:

Parliament has determined that your history of violent offending requires a very stern response to protect the public from you and to act as a deterrent to you and others. It may seem very surprising that this consequence could be required by law for an offence of this kind, but that is the law and I have no option but to enforce it.[31]

To avoid imposing a seven-year sentence for pinching a correctional officer on the bottom, Justice Toogood invoked the manifest injustice provision of the three-strikes law and determined that Raven Ramsey Campbell may seek parole after serving one third of his sentence.

Indeed, it is telling that, to date, no New Zealand judge has sentenced a defendant to serve a third-strike maximum sentence without parole. This fact suggests an autonomous, independent judiciary that prizes individualised justice. Straitjacketing judges with presumptive sentences will not work, especially if judges resent the underlying jurisprudence of three-strikes and possess a legal mechanism (e.g., manifest injustice) to blunt the full force of the law in cases where they do not believe it is warranted. One approach would to be genuinely tough on crime: 25-to-life for every third-strike, no excuses, no manifest injustice safety valve. That would deter some offenders, although the human rights implications (one death a week in custody?) would be an issue and bankrupting the government would be a high price to pay for a reduction in crime rates. More useful, presumably, would be a body of laws that have the broad support of the judiciary, that afford a greater role to victims of crime, and that make better use of non-prison sanctions.

In his 2013 article about three-strikes, Rolling Stone reporter Matt Taibbi lamented, “Like wars, forest fires and bad marriages, really stupid laws are much easier to begin than they are to end.”[32] It is an observation with which Justice Minister Andrew Little likely agrees.

References:

[1] https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/politics/2017/10/justice-minister-andrew-little-to-repeal-three-strikes-law.html

[2] https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/104608068/governments-three-strikes-repeal-killed-by-nz-first

[3] http://www.newstalkzb.co.nz/news/politics/criminal-justice-reforms-coming-in-september/

[4] Turner, M. G., Sundt, J. L., Applegate, B. K., & Cullen, F. T. (1995). ‘‘Three strikes and you’re

out’’ legislation: A national assessment. Federal Probation, 59, 16–35.

[5] http://www.nzlii.org/nz/legis/hist_bill/hcaob1906193285.pdf

[6] https://scholar.smu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.co.nz/&httpsredir=1&article=1343&context=smulr

[7] http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2002/0009/143.0/DLM135544.html

[8] http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2002/0009/143.0/DLM135543.html

[9] https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rprts05p0510.pdf

[10] http://www.corrections.govt.nz/resources/research_and_statistics/reconviction-patterns-of-released-prisoners-a-48-months-follow-up-analysis/overall-recidivism-rates-48-month-follow-up.html

[11] http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1990/0109/latest/DLM225528.html

[12] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/cbm.1993.3.4.492

[13] http://www.lao.ca.gov/2005/3_strikes/3_strikes_102005.htm

[14] https://www.americanbar.org/publications/human_rights_magazine_home/human_rights_vol31_2004/winter2004/irr_hr_winter04_shoplifting.html

[15] https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/563/493/

[16] https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/cruel-and-unusual-punishment-the-shame-of-three-strikes-laws-20130327

[17] http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-three-strikes-court-20170703-story.html

[18] https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/324660

[19] https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb02076.x

[20] http://jhr.uwpress.org/content/XLII/2/309.short

[21] http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1043986208319456

[22] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047235204000388

[23] https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/468112

[24] http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0004865814532660

[25] But see https://thespinoff.co.nz/society/14-06-2018/a-brief-history-of-new-zealands-most-absurd-three-strikes-cases/

[26] https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12063410

[27] http://www.newstalkzb.co.nz/news/crime/three-strike-rule-unfair-criminology-expert/

[28] http://www.newstalkzb.co.nz/on-air/larry-williams-drive/audio/john-pratt-three-strikes-law-is-a-travesty/

[29] https://www.maxim.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/Three-Strikes-Brookbanks-Ekins.pdf

[30] http://cardozolawreview.com/Joomla1.5/content/29-2/29.2_oleson.pdf

[31] https://offenders.sst.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Raven-Casey-Campbell-Sentencing-Notes.pdf

[32] https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/cruel-and-unusual-punishment-the-shame-of-three-strikes-laws-20130327

James Oleson is an Associate Professor in Criminology at the University of Auckland. He is an expert in contemporary criminology.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like: