By Edwin Hodge & Helga Hallgrimsdottir

Edwin Hodge and Helga Hallgrimsdottir explore the ideology behind white supremacist terrorism in light of the recent Christchurch mosque attacks.

The tragic events of Christchurch and the recent public prominence of discussions and concerns about “fake news,” privacy breaches, and electoral interference through social media share a common theme: that we do not yet fully grasp how the internet creates a space for social discourse and action and how that space creates risks and threats to democratic participation and debate, fundamental democratic values, and fundamentally, security of life. How online activism motivates the kind of senseless and inhuman brutality we witnessed in Christchurch is a pressing question.

That the Christchurch terrorist was born, bred, and motivated through online activism and debate is clear. What it took for him to set aside even the most fundamental elements of human decency to allegedly engage in an act of indiscriminate brutality is less clear. By all accounts, the terrorist wasn’t being threatened – he wasn’t personally at risk – so why travel to New Zealand to kill in cold blood? If an examination of his manifesto can tell us anything, surely it can tell us that?

Though it has largely disappeared from the internet and has since been banned by New Zealand’s Chief Censor, copies of the manifesto entitled ‘The Great Replacement’ can still be found. A great deal of the manifesto is “shitposting” – low-effort trolling designed to obfuscate, offend, and misdirect. It’s stale and juvenile and not worth the effort it takes to read. It is a confused – and confusing – melange of Far-Right conspiracy theory, fear-mongering and aggrieved entitlement. It’s exactly the sort of rhetoric you’d expect to come from the sort of person whose time was apparently spent frequenting some of the more toxic spaces of the online landscape. At its core, the manifesto reads like a contemporary re-packaging of the same dark fantasies that have long permeated racist movements; of “white genocide”; of the threat of creeping “Islamo-fascism”; of “white replacement”.

As the title of the manifesto suggests, the Christchurch terrorist seemed to be wholly committed to a common conspiracy theory among the travellers of the Far Right: replacement theory. If we are to believe the theory, white people are at risk of extinction in the face of the “higher birthrates” of non-white nations. To defend against this, “white nations” must seal their borders and expel non-white Others or risk being replaced within their own homelands by foreign invaders and their foreign Gods. Like the other fever dreams of the Far-Right, there is little to support such claims, and anyway, they rest on the faulty premise that places like America, Canada, Australia or indeed New Zealand were ever “white nations” to begin with.

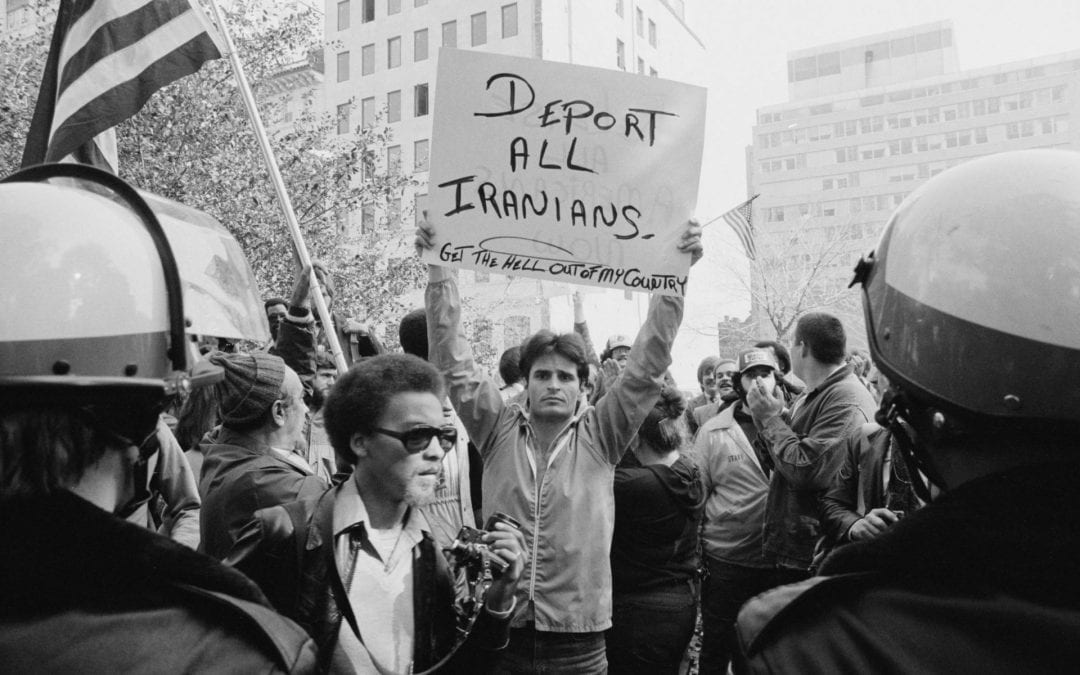

When “racial science” fails, when attempts at rebranding white supremacy as “human bio-diversity” go nowhere, white supremacists fall back on stoking fears about replacement. When alt-right and white supremacist marched in Charlottesville, Virginia, they chanted “you will not replace us”; when the Yellow Vests, a xenophobic movement here in Canada wave their placards in front of Parliament buildings, their fears of replacement can be read by all. These anxieties compel racists to act, because to them, replacement isn’t just about populations but about power. In this, the terrorist of Christchurch is no different. And this is precisely the point.

To navigate through alt-right spaces online is to immerse yourself into an unending gyre of rage, fear, and conspiracy. Beneath the weaponised irony of “meme culture” lies status anxiety which sits like a live electrical wire, exposed and ever-present. Any perceived slight against the (white) cultural identity of the West is an assault, every trend that arcs towards inclusivity a threat to “traditional” Western values. In the toxic landscape of alt-right communities, “Western Culture” as a concept approaches an almost Platonic Ideal that should not change or if it must, then it must change incrementally and at the direction of the White majority.

The communities that spawned terrorists like Mosque shooter in Quebec City, or the Toronto killer who used a rented van to manifest his rage, or the terrorist of Christchurch are ones that trade in ideas that preceded them by decades. Anxieties about race wars and “miscegenation” were core elements of The Turner Diaries, a white supremacist genocidal fantasy printed in the 1980s which was itself built on ideas that were older still. These ideas persist despite their absurdity. What has changed is the medium through which these stories and fear are spread. In the pre-internet days, Neo-Nazis, Klansmen and their ilk had little choice but to physically reach out to potential recruits by engaging in leafletting campaigns or direct recruitment. In these scenarios, recruitment numbers were low, and the personal risk to recruiters was often quite high. Now, the situation has been reversed; it has never been easier to recruit new allies to the cause, and the risk of doing so is low. For every race-baiting politician or pundit, there are a thousand nameless “anons” willing and eager to spread racist, sexist, homophobic, and transphobic images and screeds under the guise of “edgy” meme culture. Of course, at least some of these “shitposters” do so simply because they enjoy offending others, while others are more serious, but attempting to divine the individual motivations of users misses the forest for the trees. Worse, such attempts are exactly what the true believers in these communities want; what better cover for your efforts than the good-faith attempts by your ideological foes to separate the “prank” posts from the serious?

In the 1991 documentary Blood in the Face which examined the beliefs of American Neo-Nazis, Klansmen, and Aryan Nations activists, one of the men featured instructs his fellow activists to adopt a position of confused ignorance to draw potential recruits into the movement. Instead of declaring their allegiance openly, recruiters ought to pretend to have stumbled across movement literature and want the help of the potential recruit to “make sense of it”. If the recruit is sympathetic to the material, the recruiter can continue with confidence; if the target is hostile, the recruiter knows to back off and disavow the material.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because the same basic strategy can be found in the playbooks of the alt-right on sites like 4chan, reddit, or voat. Islamophobic memes are shared “as jokes” or to “trigger the libs”; they’re not meant to be taken seriously. Until they are. As researchers like Jessie Daniels have long argued, white supremacy online benefits from the ability to gradually introduce racist material through “cloaked” websites that profess to be less racist than they actually are. By masking the extent of the bigotry present, such sites can funnel potential recruits down the path of radicalisation without themselves sporting explicitly racist material.

White terrorists are radicalised in much the same way as those from other ideologies. They often travel down well-worn paths from ‘edgy’ or ‘controversial’ views to ones that are explicitly bigoted and eliminationist. They travel in spaces that systematically chip away at their ability to feel empathy for the Other, and it is a short and narrow road from that to dehumanisation. Yet our understanding of these networks remains limited, and their dynamism renders much of what we do know obsolete within months. We need devote more effort to understanding this nascent online movements, and we must take them more seriously than we have, especially now that our politicians have begun to draw support from them.

When political leaders like Canada’s Andrew Scheer appear unwilling to address the growing chorus of bigoted and xenophobic voices in the wings of their political movements, or worse, when they openly champion those ways of thinking – or even defend the extremists themselves – we move from merely tolerating intolerance to normalising it. When we are more tolerant of the rantings of the far right than we are of other groups – we all become complicit.

We are becoming enablers of Far-Right terrorism; we should be better than this. It’s not an impossible goal, as New Zealand’s own Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern has amply demonstrated. It takes courage, empathy, and a willingness to call out white supremacy wherever it takes root, and it should take next to no effort to stand in support. As the former leader of one of Canada’s political parties once wrote, “My friends, love is better than anger. Hope is better than fear. Optimism is better than despair. So let us be loving, hopeful and optimistic. And we’ll change the world.”

Edwin Hodge is a Postdoctoral Researcher with the Borders in Globalization project at the Centre for Global Studies, University of Victoria, Canada.

Helga Hallgrimsdottir is an Associate Professor in the School of Public Administration at the University of Victoria, Canada.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the views of the author(s) and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like: