By Alexander Louis

Is Auckland’s food security under threat from urban sprawl? Alexander Louis explores.

Wine growers are scrambling to breed drought proof grape varieties in California as the effects of climate change worsen. An aggressive disease decimates banana plantations in Costa Rica and destroys livelihoods, threatening over 80 percent of the worlds supply. Farmers are forced off their land as once fertile plains are transformed to barren lifeless landscapes due to increasing soil salinity in Western Australia. And in conflict zones around the world, one child dies ever minute from starvation deployed as a weapon of mass destruction.

Global headlines are frequently alarming and the implications for local populations arising from food security issues are all too often tragic. Yet the reality of famine and widespread malnutrition is not one to which most Kiwis can truly relate. While New Zealand is not immune from issues of inequality and poverty, it is still considered the fabled “land of milk and honey” by many. With fertile soils, abundant fresh water, and a varied climate, ideal growing conditions can be found for a wide range of produce; from coffee beans and pineapples in the Winterless North, to pinot noir grapes in Otago, the world’s southern-most commercial wine growing region.

Yet, in the face of increasing uncertainty in global food supply chains due to climate change, pests and diseases, environmental degradation through more intensive agricultural practices, water scarcity, and conflict, do we now risk jeopardising one of our most precious resources? On top of this, demand for fresh produce continues to grow. Already home to over one-third of New Zealand’s population, Auckland is expected to grow from its current population of approximately 1.5 million people to some 2.4 million by 2050.

And we’re not alone. Between now and 2050, global demand for food and agricultural products is projected to increase by 50 percent as a result of global population soaring to over 9 billion people. Meeting increased demand for food supply with existing agricultural land resources will be a significant challenge in and of itself, notwithstanding the loss of arable land to climate change and the environmental implications of more intensive agricultural practices.

This article looks at the historic significance of horticultural land to the cultural, social and economic growth of urban Auckland, while examining the successive “housing booms” and building trends that have bit-by-bit eaten into the productive soils on which the city is so dependant for the wellbeing of current and future generations.

A Multi-Cultural History of Horticulture in Tamaki Makaurau

The very name, Tāmaki Makaurau (Tāmaki of a hundred lovers), alludes to the fertile and resource-rich lands of the Auckland Isthmus that have enabled people to flourish and prosper for centuries. While the concept of “food security” may be relatively new, the life-giving properties of the volcanic soils and clay loams of the region have long been understood.

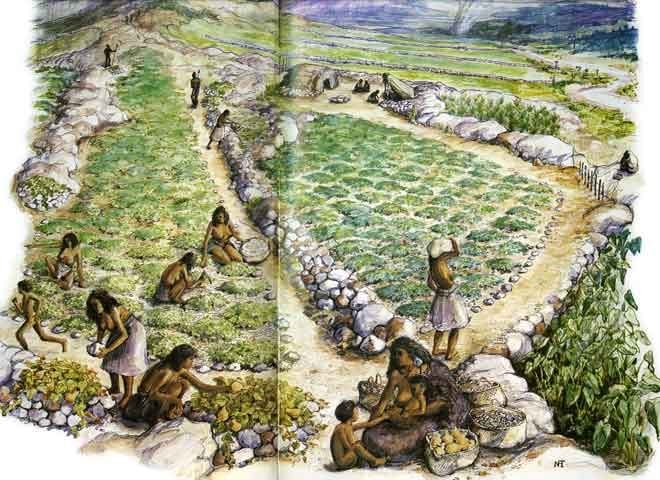

Well before the arrival of Europeans to New Zealand, and the advent of modern agricultural practices, early Maori had fine-tuned their gardening practices to suit the fertile volcanic soils of the Auckland Isthmus. A unique regional feature of gardening techniques employed by local tribes was the use of basalt rock from surrounding volcanic fields to form orderly rows and terraces within which crops were cultivated. Once a prolific feature of the landscape in areas such as Maungakiekie (One Tree Hill), Maungarei (Mt Wellington) and Maungawhau (Mt Eden), most of these field systems have succumbed to urban development over the last 150 years, a trend that shows no signs of abating. It was the Maori gardeners, however, who were the first commercial growers of vegetables in New Zealand, supplying early European whalers and traders in the early 19th century.

An artist’s impression of a garden in Auckland in the 1700s

Source: Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

The number of European settlers in South Auckland began to increase in the mid-19th century as large tracts of land became available for purchase. Through this process, the densely bush clad landscape was quickly cleared to expose the productive volcanic soils beneath. The favourable horticultural properties of the land were soon realised and it was not long before the importance of the area to the growing metropolitan centre in the north was cemented.

As the gold rush in Otago abated, the descendants of New Zealand’s first Chinese Immigrants moved north in search of new opportunities. By the turn of the 20th century Chinese market gardeners had begun to establish themselves in Auckland, taking advantage of new infrastructure such as roads and railways that connected Pukekohe, then still very much a rural outpost, with urban markets.

The early 20th century saw an increase in Indian immigrants settle in Pukekohe. Indian market gardeners worked hard as labourers, eventually leasing land of their own and gaining a strong commercial foothold in the area and standing within the local community. This was despite extreme discrimination from Europeans in the first half of the 20th century, as illustrated by the 1926 article in the Franklin Times titled “Our Asiatics,” which lamented the economic displacement of industrious white potato farmers by Hindus, who were deemed “mentally and morally incapable of real civilisation.”

Loading Ravji Hari’s vegetable truck, Pukekohe

Source: Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

Up until the early 20th century, the growth of market gardening had been steady, but gradual. The First and Second World Wars, and preceding periods of technological advancement, changed that. During World War II, in particular, the growing of vegetables for New Zealand and American troops in the Pacific resulted in a significant increase in the amount of land used for vegetable cultivation. Huge amounts of resources were dedicated to the “war effort” during this time, laying the foundation for the rise of future commercial horticultural industries. Rapid technological development and stable opportunities for international trade in the 1950s and 60s, saw the export of canned goods from New Zealand overtaken by frozen and dried produce, which could be shipped around the world to their destination in purpose built containers.

Horticulture is now one of New Zealand’s largest primary industries, contributing $5.68 billion to the economy in 2017 and experiencing rapid growth in export value over the last five years. While making up a relatively small portion of national horticultural land by area (approximately 2%), the elite soils of the Pukekohe growing hub, on the doorstep of the country’s largest and fastest growing city, have historically played an important role in supplying fresh produce to a burgeoning urban population.

Home, Garden, Sunshine

The first settlements in Auckland clustered around the port at the bottom of what is now Queen Street. Small wooden weatherboard cottages soon creeped up the gullies to form the first inner city suburbs or Parnell, Grafton, and Newton, quickly spilling into Ponsonby and Grey Lynn. In those early years, development was concentrated around the inner city due to limited means of transportation. Horse drawn trams were still in use up to 1902.

Early Subdivision, Ponsonby, Auckland.

Source: Auckland Council GeoMaps 2017 Aerial Photograph

The above aerial photo shows a tightly packed inner-city subdivision on Renall Street and Russell Street, Ponsonby, reflective of Auckland’s early residential development in the late 19th Century. These sites typically have an area of around 200m2, are accessed off narrow streets, and were constructed well before off-street parking was a consideration.

As means of transport improved, such as ferries serving Devonport, electric trams serving fringe suburbs such as Mount Eden and Balmoral, and commuter rail lines to the satellite towns of Onehunga and beyond, the city slowly began to expand. By the 1920’s and 30’s, Auckland’s love affair with the Californian bungalow had begun. These quintessential dwellings were comparatively spacious three-bedroom weatherboard houses, typically set on more generously proportioned sections. The below image shows an aerial photo of King Edward Avenue in Mount Eden, representative of subdivision in the early 20th century: wide tree-lined streets laid out in a grid pattern with residential lots approximately 600sqm in area.

Early Suburbs, Mount Eden, Auckland.

Source: Auckland Council GeoMaps 2017 Aerial Photograph

The 1940’s and 50’s saw a growing number of working-class families with access to private automobiles and cheap fuel, hungry for their own quarter acre of paradise. Priced out of leafy fringe suburbs and seeking refuge from the densely populated and often unsanitary conditions of Auckland’s original inner-city areas, large numbers of the working class began to move out to the relative tranquillity of the suburbs.

Railways poster promoting suburban life, 1930s

Source: Te Ara – The Encyclopaedia of New Zealand

Coinciding with this drift to the suburbs, the First Labour Government of New Zealand had already commenced a large-scale state housing programme, announcing a budget in 1936 to enable the construction of 5,000 new dwellings across hundreds of acres of greenfield land. New state housing areas were established on the outskirts of existing urban areas, partly to take advantage of cheap land, but also because it was thought that the suburbs offered a healthier lifestyle than the inner city.

The image below shows an aerial photograph of Oranga, a state housing development from the 1940s. Rockfield Road forms a defined, albeit temporary boundary, between suburban land and rural land to the east (top). The layout of this subdivision shows a shift toward irregular and inefficient block layouts, with houses located centrally within the site and provision for onsite car parking. Before the days of supermarkets and reliable cheap fresh produce, it was also important to set space aside for the family vegetable garden.

Early State Housing, Oranga, Auckland.

Source: Wikipedia

During the 1950s and 1960s, an ever-increasing rate of urban sprawl began to result in greater conflicts with rural land uses in areas such as Māngere and Panmure. The below aerial photographs show the horticultural areas of Panmure in 1940 (top) almost entirely replaced by suburban development (much of it state housing) some 20 years later in 1959 (bottom).

Source: Auckland Council GeoMaps, 1940 and 1959 Aerial Photography

Over the coming decades, this trend continued. Pressure for more and more low-density housing eventually swallowed up areas that had been intended for greenbelts. The 1950’s saw major investment in infrastructure for private motor vehicles, including motorways and the Auckland Harbour Bridge, which were pursued in favour of public transport.

Recent Subdivision, Dannemora, South Auckland.

Source: Auckland Council GeoMaps 2017 Aerial Photograph

Auckland’s sprawl marched on during the latter part of the 20th century and the early 2000’s, with further growth occurring on the periphery in areas such as Flat Bush, East Tamaki, Botany, Albany, Greenhithe and Orewa well into the 2000’s. Development continued to reflect Aucklanders’ appetites for large sections and their dependence on private automobiles as the primary means of transport. As the city continued to swell, residential areas become more disjointed from amenities and public transport infrastructure. The image (above) shows the subdivision of Dannemora in Auckland’s South East. Site sizes have increased to in excess of 800m2, with much of this is now occupied by larger two storey dwellings and double garages for parking. Cul-de-sacs and irregular block layouts remain prevalent in an effort to create quiet suburban neighbourhoods, at the expense of more efficient land use and better pedestrian connectivity.

In recent times, particularly since the implementation of the new Auckland Unitary Plan, consumer demands, architectural trends, land and building costs, and more enabling planning provisions have seen a shift away from the traditional land-hungry forms of suburban residential development. It’s now not uncommon to see site sizes of 180m2 or less in new residential subdivisions and a mixture of terraced, attached and detached medium density typologies within more regular grid based block layouts.

But, with the only remaining greenfield land available for future expansion being on the fringes of the existing urban limits, has this paradigm shift in development occurred too late? More recent periods of development have threatened some of the region’s best quality growing land. Auckland Council estimate that between 1975 and 2012, nearly 10% of Auckland’s best quality horticultural soils have been converted to urban area, equating to some 10,399 hectares. The image below shows a recent subdivision in Belmont, Pukekohe that is partially constructed over, and adjacent to, productive horticultural land.

Recent Subdivision, Belmont, Pukekohe

Source: Auckland Council GeoMaps 2017 Aerial Photograph

A Precious and Unique Resource

Approximately 7,000 hectares of land are now used in Auckland for horticultural production. Crops range from staples, such as onions and potatoes, to increasing numbers of vineyards in Auckland’s west, north, and the Gulf Islands. However, Auckland’s most favourable growing soils are found in and around Pukekohe.

Auckland Council land and soil scientist Fiona Curran-Cournane explains that geographic, topographic, and climatic characteristics make South Auckland uniquely suited to outdoor horticultural activity. Firstly, the area is overlain by extremely fertile soils that date back to a volcanic eruption in the central plateau 250,000 years ago. Secondly, the topography of the area is relatively flat to moderate, with little steeply sloping erosion-prone areas. Thirdly, the climate is just right: far enough north to avoid the worst of the frosts that affect lower latitudes, but far enough south to avoid the pests that plague warmer regions. The combination of these factors make Pukekohe one of the more desirable growing regions in the country, able to sustain horticultural activity all year round.

Soil scientists use the Land Use Capability (LUC) Classification to rate the productive value of land: LUC 1 being elite horticultural areas and LUC 8 being land with no agricultural value. The only LUC 1 land in Auckland is exclusive to South Auckland and Pukekohe. While the “land of milk and honey” myth prevails, Curran-Cournane confirms that most productive soils in New Zealand are in fact LUC 6 and below, which are only suitable for forestry or pasture. Effective outdoor horticultural activity relies on the high-quality soils near the top of the scale, LUC 1 to 3.

So, what might be the impacts if further urban expansion results in continued loss of horticultural land?

There are a number of environmental consequences associated with increased urban development and the loss of productive land. Firstly, relocating horticultural activities from Pukekohe likely means transferring horticultural activities to less productive soils. Growing food on lower-quality soil requires increased fertiliser, which in turn will generate more nitrate runoff into waterways. Another implication is greater food miles. Food transport is a major source of CO2 emissions, with studies showing that buying local can be more important than buying green. Horticultural production in South Auckland has always been well placed to cater to the needs of the nearby urban population. The loss of horticultural land proximate to cities means that food has to travel further to reach consumers.

Urban development also has the potential to affect the productivity of existing horticultural areas. As the city spreads, so too do impervious surfaces and stormwater infrastructure, which impede and intercept rainfall before it can recharge groundwater reservoirs. Bore water from these reservoirs is essential for growers in Pukekohe during the drier summer months. Furthermore, increased residential and commercial activity creates greater competition for existing reticulated water supply.

The loss of horticultural land would also have significant economic effects. Horticulture is a major contributor to the Auckland economy, directly generating $86 million per year in revenue and providing 1,458 full-time equivalent jobs. The projected loss of productive horticultural land could have significant economic impacts. Deloitte released a report in August 2018 identifying the following potential economic implications over the next 25 years:

- A loss to the economy of between $850 million and $1.1 billion in today’s dollars.

- The loss of between 3,500 and 4,500 full-time equivalent jobs.

- A reduction in the volume of fruit and vegetable production of between 46 and 55 percent.

- Increased cost of fresh produce of between 43 and 58 percent.

The potential direct and indirect implications arising from a loss of productive horticultural land on the social fabric of the area also needs to be considered. For over a century, and across numerous generations, a multicultural community of growers and associated service providers have established in South Auckland. The physical loss of horticultural land, the uncertainty around the extent of future urban encroachment, and the effect of increasing conflict between residents and producers at the interface of competing land uses, all serve to erode the social stability of existing agricultural communities.

The fertile soils and favourable growing climate that combine to create the horticultural areas in Auckland’s South has contributed to and sustained the growth of the Auckland region from its earliest days of settlement through to more recent periods of rapid growth and expansion. However, the continued growth of Auckland is occurring increasingly in conflict with the sustainability of the very resource that has allowed it to flourish, with wide-ranging environmental, economic and social implications. With food security becoming a growing issue of international concern, and growing pressure on existing food systems, we must think very carefully about protecting what remains of this unique and precious resource from future expansion.

This article has been published under a pseudonym. The author is a graduate student at the University of Auckland.

Disclaimer: The ideas expressed in this article reflect the author’s views and not necessarily the views of The Big Q.

You might also like:

What is the future of cities? 🔊

Q+A: What are the politics of food insecurity?